USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists extract as much insight as possible from historic accounts of eruptions, and then combine that information with current observations of activity to improve our understanding of how Hawaiian volcanoes work. ADVERTISING USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory

USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists extract as much insight as possible from historic accounts of eruptions, and then combine that information with current observations of activity to improve our understanding of how Hawaiian volcanoes work.

Recent Volcano Watch articles compared past records for topics such as the Halema‘uma‘u lava lakes through time, the Mauna Loa lava flow that threatened Hilo in 1881 and the Kilauea lava flow (June 27 lava flow) that recently threatened Pahoa.

Further detective work on the Mauna Loa eruption that started Nov. 5, 1880, reveals witnesses saw three separate lava flows advance from the volcano’s Northeast Rift Zone in the first few days of the eruption.

The first flow (the Mauna Kea branch) advanced north into the Saddle area and stalled a few days later. The second flow (the Ka‘u branch) moved toward Kilauea caldera and also stalled several days later. The third and last lava flow from this eruption (the Hilo branch) advanced toward the northeast and, by summer of 1881, threatened Hilo (this flow was the subject of our March 26 Volcano Watch).

Until recently, all three branches of the 1880–81 lava flows were represented on geologic maps of Hawaii Island. But an ongoing remapping effort for Mauna Loa has produced some surprises — one of which is that the flow mapped as the first and northernmost 1880 lava (the Mauna Kea branch) actually was erupted a few years later — in 1899.

The true identity of this flow was determined by matching its chemistry with other lavas that are known with certainty to have been erupted in 1899. It would be hard to challenge such definitive geochemical evidence, but we still don’t know what happened to the reported Mauna Kea branch of the 1880–81 eruption.

Going back to newspapers of the time, one can find clear descriptions of the three flow branches, with the first branch advancing north into the Saddle just north of the Mauna Loa 1855 lava flow (right where it formerly was mapped). One of these accounts described a trip by a pair of explorers who traveled from the vent high on the rift zone down into the Saddle along the Mauna Kea branch of the flow.

Of course, GPS didn’t exist in the 1880s, so these travelers, at best, might have had a barometer that estimated elevation using variations in air pressure.

Some travelers recorded approximate elevations of landmarks that we can recognize today. A few others published sketch maps in the newspaper along with their harrowing accounts of the eruption.

In addition, government surveyors of that era were working hard on mapping the Hawaiian Kingdom using triangulation and chaining distances (literally using a chain of known length and counting how many “chains” it took to replicate the distance).

Toward the end of the 19th century, many areas were mapped, including the Saddle between Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. There was a lot of sketching “by eye” that went into mapping the Mauna Loa side of the Saddle, but it still was useful.

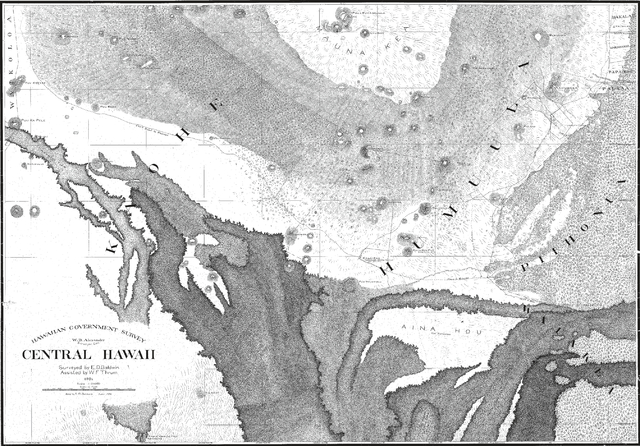

Some of these wonderful old maps can be found online at the Hawaii State Archives (http://ags.hawaii.gov/survey/map-search/). For this particular quest, registered map number 1718 (from the year 1891) shows the first branch of the 1880–81 lava flows (a dark, thumb-shaped lobe peeking up from the bottom of the map) lying on 1855–56 lava.

These maps confirm there was a Mauna Kea branch of the 1880–81 eruption, but that, in fact, it might only have been about 13 km (8 mi) long instead of 20 km (12 mi) long, as the map showed until recently.

With further mapping, the Mauna Kea branch might have been found again — under the later 1899 flows or to the side of the 1855–56 flow. The challenge now is to see whether we can identify the Mauna Kea branch in remaining kipuka within the 1899 flow or nearby areas.

Boots-on-the-ground field work still is the best way to ascertain the geologic record of a volcano. However, geologic questions sometimes can be answered by good old archival research, so we are fortunate so many archives now are available online.

Kilauea

activity update

Kilauea’s summit lava lake level fluctuated during the past week, with changes in summit inflation and deflation, but remained well below the rim of the Overlook crater vent. During the past week, the lake ranged between 40 and 55 m (130–180 ft) below the current floor of Halema‘uma‘u.

Kilauea’s East Rift Zone lava flow continues to feed widespread breakouts northeast of Pu‘u ‘O‘o. Active flows slowly are overplating and widening the flow field, and remain within about 8 km (5 mi) of Pu‘u ‘O‘o.

No felt earthquakes were reported on the Big Island in the past week.

Visit the HVO website (http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov) for past Volcano Watch articles, Kilauea daily eruption updates and other volcano status reports, current volcano photos, recent earthquakes, and more; call (808) 967-8862 for a Kilauea summary update; email questions to askHVO@usgs.gov.

Volcano Watch (http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/) is a weekly article and activity update written by scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey`s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.