Some low-lying major roadways and beloved landmarks on Hawaii Island are destined to sink beneath the waves, according to a new study on sea-level rise.

The study, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reports long-term impacts of carbon dioxide emissions on sea-level rise will vary depending on emissions controls put in place in the coming decades, while also showing inundation in areas of many U.S. cities already is inevitable, even if the world were to adopt the very highest standards for cutting emissions right now.

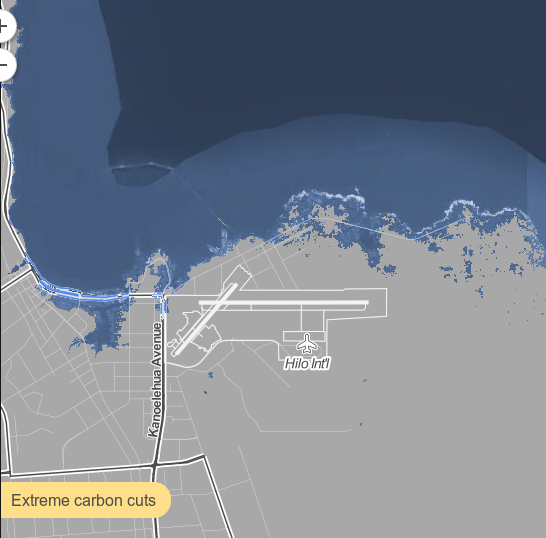

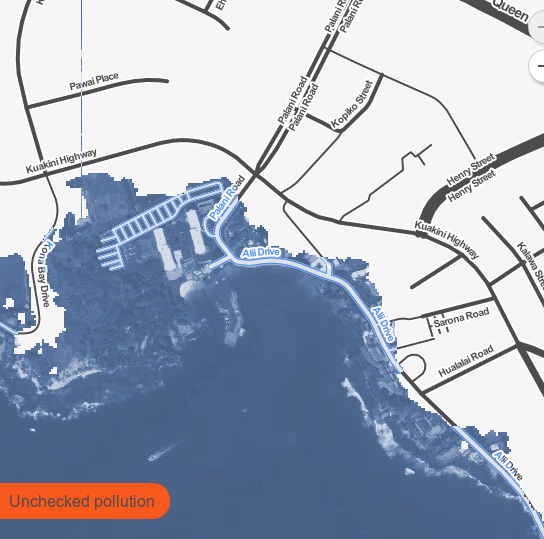

Accompanying the research paper, a map at choices.climatecentral.org allows viewers to explore topographic regions across the country to see how different global warming scenarios will impact areas.

Low-lying cities such as Miami and New Orleans will be impacted severely in the long term, no matter what is done to address climate change, the study found. The state of Florida would experience the most extreme impacts overall, with California, Louisiana and New York also being heavily inundated by rising sea levels.

Luckily, because of the steep nature of the Hawaiian Islands, the impacts will not be as extreme, according to Steven Colbert, an assistant professor with the University of Hawaii at Hilo’s Marine Science Department.

“Our low-lying areas represent a fairly small area right along the coastline,” he said.

However, many of Hawaii’s cultural and natural treasures reside in low-lying areas, Colbert said.

“We have so many cultural resources that are tied in with our shoreline, like Coconut Island in Hilo, to Honaunau over in Kona. These places are right at sea level, and they’re the first places being lost with sea-level rise,” he said.

Even in the best-case scenarios, areas such as Keaukaha, Banyan Drive, Kamehameha Avenue and Waiopae on the east side of the Big Island, along with Alii Drive in Kona, largely will be submerged sometime after the year 2100, according to the projections.

It will be a long, slow process, Colbert said, with extreme weather events such as tsunamis and hurricanes forcing reactions by communities to move inhabited areas away from the water.

“I think that sea-level rise is inevitable, and how we’re going to adjust to it is going to be something that each of these communities is going to have to deal with in their own ways,” he said.

“There will be short-term solutions, like putting homes up on stilts and building higher, rather than moving away from the shoreline. But those are just short-term possibilities. There’s going to be long-term inevitability of these neighborhoods, which are going to be underwater. People need to decide, what do they value in their community and on this island. What needs to be done to preserve those things they value?”

The study found more than 20 million people in up to 1,825 municipalities in the U.S. are endangered by sea encroachment in the long term.

“Under aggressive carbon cuts, more than half of these municipalities would avoid this commitment if the West Antarctic Ice Sheet remains stable,” the report reads.

“Similarly, more than half of the U.S. population-weighted area under threat could be spared. We provide lists of implicated cities and state populations for different emissions scenarios and with and without a certain collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Although past anthropogenic emissions already have caused sea-level commitment that will force coastal cities to adapt, future emissions will determine which areas we can continue to occupy or may have to abandon.”

The study, titled “Carbon Choices Determine US Cities Committed to Futures Below Sea Level,” was authored by Benjamin H. Strauss and Scott Kulp of Princeton University’s nonprofit organization Climate Central; and Anders Levermann from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

Email Colin M. Stewart at cstewart@hawaiitribune-herald.com.