Take a walk down Mamane Street in Honokaa and it’s easy to see the Big Island’s sugar plantation history in the facades of the single-wall buildings that line the road. ADVERTISING Take a walk down Mamane Street in Honokaa and

Take a walk down Mamane Street in Honokaa and it’s easy to see the Big Island’s sugar plantation history in the facades of the single-wall buildings that line the road.

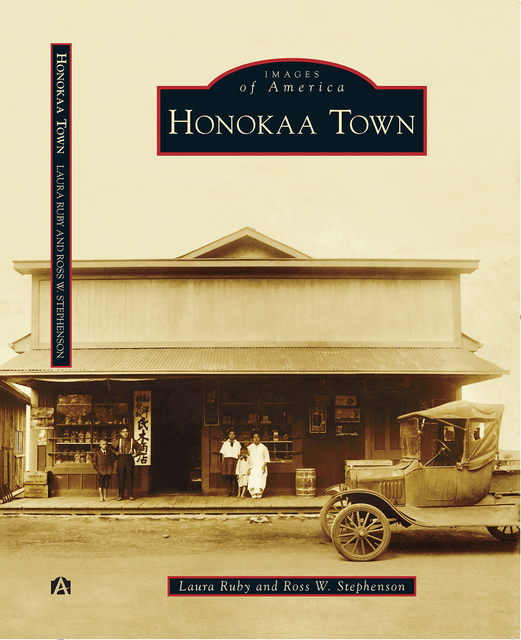

A new book published last month as part of Arcadia’s Images of America series takes a deeper dive into that history, telling the stories of the generations of plantation workers who made their lives in Honokaa.

The book, “Honokaa Town,” is the latest component of a broader effort to preserve the cultural heritage of the area and ensure its stories are around for the next generations to discover. The Historic Honokaa Project builds on a similar preservation campaign that launched in the 1970s.

Most recently, organizers have worked to restore buildings and place others on the National Register of Historic Places.

“Honokaa Town” co-author Ross Stephenson, former historian for the Hawaii State Historic Preservation Division and keeper of the Hawaii Register of Historic Places, said the ultimate goal is to have people be aware of the area’s “magnificent history.”

“It’s basically to celebrate who we are,” he said. “We want the next generation … to learn about who they are, where they came from.”

“Honokaa Town” is the second time Stephenson has partnered with Laura Ruby to co-author a book. Ruby, a recipient of the Hawaii Individual Artist Fellowship and Living Treasures of Hawaii Award, taught arts at the University of Hawaii at Manoa for 34 years.

The pair’s first collaboration was “Honolulu Town,” published by Arcadia in 2012.

“We knew the people were familiar with this kind of (book) format,” Stephenson said. Working with Arcadia once more “fit our idea of a book that would explain things, but also would be convenient enough to carry around as a guidebook.”

The book is oriented around location, with chapters starting “On The Way to Honokaa” and ending “Up Lehua to Waimea.” A historic map helps readers place their present-day surroundings in context.

Even with their previous book experience, Stephenson and Ruby found that gathering the raw material that would become “Honokaa Town” was complicated, involving more than just a trip to the archives.

“It’s more of a challenge because we’re very Honolulu-centric in this state,” Stephenson said. “It means doing a lot of extra work out in the community, in the field. My wife is from Paauilo and that certainly helped open some doors.”

Many images came from collections at the North Hawaii Education and Research Center. But just as important was making personal connections.

“When people found out what we were doing, they would come in and volunteer their family photographs,” Stephenson said.

As well as their stories: stories of how difficult it once was to move supplies in the area; how trucks changed the plantation system; and how some of the engineers who worked on the Hamakua Coast went on to build California’s aqueduct system.

For Stephenson, it was the quiet stories of plantation life that had the most impact.

“The small-town shop owners who came off the plantations and started their own businesses, and raised their families and looked at the long term so that their kids could get an education — those people are real heroes,” he said.