An entire generation in Hawaii has grown up with no memory of the Xerox building mass shooting in Honolulu that killed seven people in 1999.

And although the public is barraged by media images of the aftermath of mass shootings in places as far flung as San Bernardino, Calif., and Newtown, Conn., Hawaii has the lowest firearms death rate per capita in the U.S. — 2.6 per 100,000 population, according to the latest U.S. Census statistics.

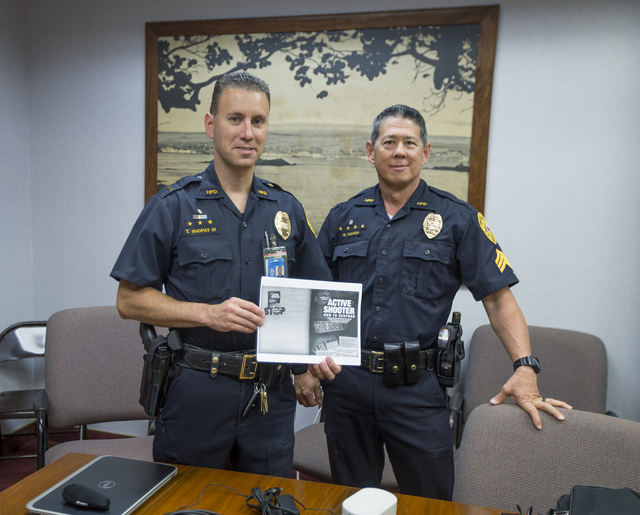

Lt. Thomas Shopay of the Hawaii Police Department’s Special Response Team has given about 50 presentations on how to survive an “active shooter” to businesses, schools, churches and other community groups since 2013. He says it’s important to realize that even here, a place some consider paradise, the unthinkable can occur.

“It’s highly unlikely this will ever happen to you, but you can’t say it will never happen, so you’ll want to prepare yourselves,” Shopay said during a presentation at a Hilo business. “Active shooter incidents are low probability but very high risk. The high risk is that somebody’s going to lose their life. That’s not an acceptable outcome.

“The reality is if an active shooter walks into a building or some sort of organization, there are going to be some casualties, because the active shooter is going to know what they’re intending to do before they get there.”

Shopay said a mass shooting “is rarely a random act,” and the shooter could be anyone. Sometimes, it’s a disgruntled employee or former employee, as in numerous post office shootings across the U.S. in the 1980s, ’90s and early 2000s, or in the case of Byran Uyesugi, the Honolulu Xerox shooter who’s serving a life sentence.

Shopay said mass shooters, including Uyesugi — a service technician who was upset about being trained on new equipment — leave clues that if picked up in time, could avert a tragedy.

“It wasn’t out of the blue this happened,” Shopay said. “He was training on the new system, and he was very resistant to that. And there were other issues.”

Shopay said mass shooters know their actions likely will end badly for them, but they don’t care because survival usually isn’t part of their plan. He called it a “vengeful mindset of, ‘I’m going to make an example, and the whole world needs to know how horribly I was treated.’”

“Their goal is not to have one or two casualties, because that’ll make the local news,” he said. “They don’t want to have five or six. That may make the state news. They want to draw attention to their cause by having more casualties than the last person. Get something scary, get some big numbers out there, and the world will see the injustices, real or perceived.”

On Dec. 2 in San Bernardino, 14 people were killed and another 22 seriously injured, but a neighbor didn’t come forward with information about the shooters — a husband and wife who were also killed in a shootout with police — because she didn’t want to “be perceived as racist or something else,” Shopay said.

“By her not providing the information to be investigated or looked at, some bad things happened. That’s something she has to live with,” he said.

Shopay said people who survive mass shootings usually do so because they have a plan.

The plan need not be complicated, but one should think ahead, be aware of escape routes and hiding places, trust one’s instincts and, if the time comes, assess three options — run, hide or fight, in that order.

“If you’re not there, nothing bad is going to happen,” he said. “But you might not have that option. If you’re in this room, and you hear gunfire, and you can’t pinpoint where it’s coming from, you might not want to run into it.”

And if you do escape, Shopay said, “As soon as you get out, call 911. Activate the response and shorten that (time) gap for everybody who wasn’t as lucky as you to get out.”

The second best option is to hide, but not by huddling under a table, as a Colorado teacher instructed students in the library to do during the Columbine High School shootings in 1999. Several students who followed that advice were killed.

“It’s basically fortifying your location,” Shopay said. “We’re in this room, and something is happening out there. This door is getting closed, we’re putting the table up against the door to barricade the location as much as possible and getting down behind the table, so if a bullet comes through this wall, it has to go through a bunch of stuff before it touches us.”

And once barricaded inside a room, resist the temptation to let others inside.

During the 2007 mass shooting at Virginia Tech, the gunman, student Seung-Hui Cho — who killed 32 people before turning a gun on himself — knocked on walls of locked rooms pretending to be someone trying to escape the carnage and asking to be let in.

“They trusted their instincts,” Shopay said. “They didn’t know who was out there. They stayed quiet. They stayed safe. They stayed alive. Good move.”

Shopay said red flags were overlooked at Virginia Tech prior to the massacre. He said students in a writing class were disturbed by the content of Cho’s essays, voiced concerns about their inappropriateness, and were told in America, Cho was free to write what he pleased.

“Some of the students said, ‘You’re right, and I can do whatever I want. I’ll take the class next semester, when I feel safe,’” Shopay said. “They trusted their instincts. They made a good decision. So that class size dwindled, over time, to just a few in that class. The few in that class were in a state of denial or didn’t trust their instincts and didn’t make a good decision. Those who trusted their instincts are still around.”

Sometimes, the only option is to fight the shooter — but it should be the last resort. Shopay cited the example of Patricia Maisch, then 61, who helped stop Jared Loughner after he had killed six people and wounded 13 others, including then-Arizona U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, in a Safeway parking lot in Tucson, Arizona, five years ago.

Realizing she couldn’t run and had nowhere to hide, Maisch lay on the asphalt. When Loughner was near her and dropped some ammunition and tried to reload, she grabbed the magazine and helped others, including Joe Zamudio, subdue him. Zamudio, who was licensed to carry a concealed handgun, by mistake almost shot one of the other heroes, who had taken the gun from Loughner.

“Patricia Maisch is a hero,” Shopay said. “I really believe everybody has the potential for being a hero, and I define a hero as somebody who makes really good decisions at a very critical time.”

Businesses and organizations can arrange active shooter presentations by calling Chief Harry Kubojiri’s office at 961-2244.

Email John Burnett at jburnett@hawaiitribune-herald.com.