In previous Volcano Watch articles, we addressed the origin of the Ninole Hills on the southeastern flank of Mauna Loa. These hills are a prominent group of flat-topped ridges towering over nearby Punaluu Beach Park.

For a long time, geologists were perplexed about the formation of the Ninole Hills and what they represented. The steep sides of the heavily vegetated hills are cut with canyons caused by thousands of years of erosion. Through age-dating of the rocks, the hills were estimated to be approximately 125,000 years old.

Several theories have been put forward to explain the formation of the Ninole Hills.

According to one, they are the remnants of an older summit of Mauna Loa or its predecessor volcano, Mohokea. In another theory, faulting and landslides are thought to have formed the hills.

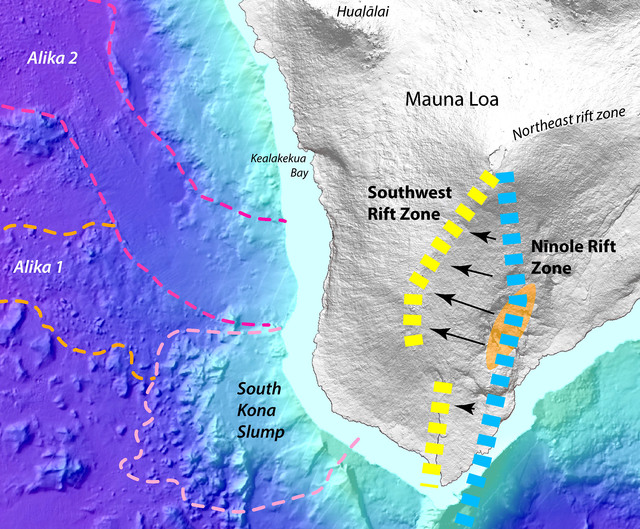

Recent studies proposed hypotheses about the Ninole Hills once being the site of active volcanism. Based on regional gravity data, one study suggests the existence of a previously unrecognized rift zone extending south of Mauna Loa’s summit toward the hills. Seismic studies suggest the Ninole Hills might be a failed rift zone, extending from Mauna Loa’s summit, through the hills, and past the coastline toward Pu‘u‘omahana (Green Sands).

In 2013, USGS scientists and colleagues from academia embarked on a project using microgravity surveys to understand the origin of the Ninole Hills and distinguish among competing hypotheses. We chose microgravity because each of the proposed mechanisms for the formation of the Ninole Hills should produce distinct gravitational signatures because of differences in subsurface structure and/or modification.

Measuring gravity helps scientists understand the types of rocks that might underlie the area. Using a device called a gravimeter, scientists can measure the amount of gravitational pull on a certain area.

Gravitational pull varies depending on location on the Earth’s surface, as well as the types of rock that make up the area. Lava rocks — for example, those from flows near Kalapana — are low-density and, thus, have lower gravity values. The rift zones and summits of volcanoes contain denser rocks because of repeated intrusions that result in magma cooling below ground, so they have a higher gravity signature.

With the microgravity survey, we found an elongate, northeast-to-southwest positive, or high, gravity anomaly in the region of the hills. If the Ninole Hills represent slump blocks and landslide scarps, they should generate a gravitational low because lava flows and faulted surfaces are characteristically low-density. Therefore, this hypothesis is not consistent with the data.

If the Ninole Hills are the location of the summit area of an older volcano, the anticipated gravity signal would be circular and centered above a dense intrusive complex. But the microgravity data instead show an elongate intrusive complex.

The Ninole Hills and Mauna Loa lava flows show no appreciable difference in chemical composition. So, the possibility that the Ninole Hills are a separate and different volcano was ruled out.

What does the geology of the hills tell us about their origin?

During the course of recent geologic mapping, we noted several north-trending dikes. These dikes — vertical feeders of magma from the subsurface storage reservoir to the surface — were exposed in road cuts on the flanks of several of the Ninole Hills.

Research on other Hawaiian volcanoes shows the number of dikes drops rapidly with increasing distance from the rift zones. The presence of dikes in the Ninole Hills and the elongate gravitational high are consistent with the notion they were once part of a rift zone.

If the Ninole Hills do represent an old rift zone, why was it abandoned? Spreading because of gravitational settling, faulting and landsides could be the cause.

Several debris flows and landslides — the South Kona Slump and the ‘Alika-1 and ‘Alika-2 landslides — exist on the west coast of the Big Island. The ‘Alika-2 slide, which is approximately 127,000 years old and comprises the Kealakekua region of West Hawaii, was contemporaneous with Ninole Hills activity.

Putting all of this together, we conclude the Ninole Hills are a failed rift, and that mass-wasting events on Mauna Loa’s western flank most likely caused the abandonment of the rift, leading to the westward migration of Mauna Loa’s present Southwest Rift Zone.

Volcano activity update

Kilauea continues to erupt at its summit and East Rift Zone. During the past week, the summit lava lake was relatively stable, with the lake level about 28 to 32.5 m (92 to 107 ft) below the vent rim within Halema‘uma‘u Crater.

On the East Rift Zone, satellite imagery acquired March 23 showed scattered lava flow activity within about 8 km (5 mi) of Pu‘u ‘O‘o. These flows were not threatening nearby communities.

Mauna Loa is not erupting. Seismicity remains elevated above long-term background levels, but no significant changes were recorded during the past week. GPS measurements show continued deformation related to inflation of a magma reservoir beneath the summit and upper Southwest Rift Zone of Mauna Loa, with inflation recently occurring mainly in the southwestern part of the magma storage complex.

Two earthquakes were reported felt on Hawaii Island during the past week.

At 9:28 a.m. March 21, a magnitude-2.9 earthquake occurred 10.6 km (6.6 mi) north of Kawaihae at a depth of 23.4 km (14.6 mi). At 6:43 a.m. March 20, a magnitude-4.6 earthquake occurred 14.3 km (8.9 mi) southeast of Waikoloa at a depth of 32.4 km (20.1 mi).

Visit the HVO website (http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov) for past Volcano Watch articles, Kilauea daily eruption updates, Mauna Loa weekly updates, volcano photos, recent earthquakes info, and more; call for summary updates at 808-967-8862 (Kilauea) or 808-967-8866 (Mauna Loa); email questions to askHVO@usgs.gov.

Volcano Watch (http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/) is a weekly article and activity update written by scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey`s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.