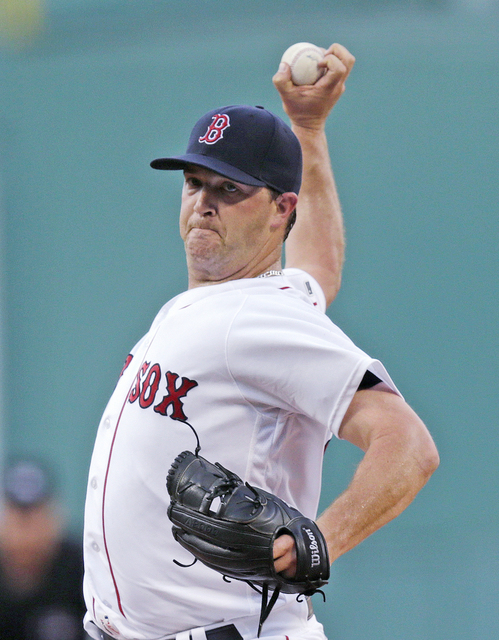

MLB: Red Sox made Wright choice in trading for UH-Manoa alum

The Boston Red Sox were stumbling in the summer of 2012, on their way to a last-place finish in the American League East. While contenders acted boldly before the trading deadline, snagging Zack Greinke, Hunter Pence, Hanley Ramirez, Ichiro Suzuki and other stars, the Red Sox made a more subtle transaction: They shipped a fading first-base prospect, Lars Anderson, to the Cleveland Indians for a Class AAA knuckleballer named Steven Wright.

ADVERTISING

Anderson has not appeared in a major league game since. Wright is headed for the All-Star Game in San Diego on Tuesday with a 10-5 record and a 2.68 earned run average. The Indians have a dazzling rotation and have not missed Wright, but surely they must regret the deal — right?

“I look at that a little bit differently,” said Chris Antonetti, the Indians’ president for baseball operations, who made the trade with the former Boston general manager Ben Cherington. “Steven’s career and life could have been very different had he not ended up in Boston.

“Ben and I talked openly about that — they had resources there, in Tim Wakefield, to be able to help Steven’s development. He continued to make progress and get better, and they were patient enough to bear the fruits of all that work he put in. It’s pretty cool, and I’m thrilled for him.”

Wright learned the knuckleball at age 9 from a pitching instructor, Frank Pastore, a former Cincinnati Reds right-hander. Wright was good enough as a conventional pitcher to be drafted in the second round by Cleveland in 2006 out of the University of Hawaii, but by 2010 he had stalled at Class AA Akron.

One day that summer, an Akron starter, Scott Barnes, was scheduled to throw a bullpen session. Wright beat him there and fooled around with Pastore’s pitch.

“He was taking forever, so I just jumped up on the mound and started throwing them,” Wright said earlier this season. “I was searching for an out pitch, and then they saw that and they were like, ‘That’s it.’ So I started throwing it as an out pitch, and it kind of just evolved into where it is now.”

The Indians were excited about the idea. Mark Shapiro, their former president, told Wright, now 31, that age no longer applied to him. If he concentrated on the knuckler, Wright said Shapiro told him, “To us, you’re 21 again.”

But the Indians could not stop the clock on Wright’s minor league service time. They brought in Tom Candiotti, a former Cleveland knuckleballer, to help Wright the next spring as he prepared to start over in low Class A. But Wright was facing minor league free agency after the 2012 season, and a 2.49 ERA in Class AA was not enough to persuade the Indians to keep him.

“We were at that point where we had to make a decision on our roster, and the Red Sox had more flexibility,” Antonetti said. “They did a great job identifying a guy they thought could be successful, and they had the resources to help him on that path.”

Essentially, the Indians sent Wright to a knuckleball finishing school, with Wakefield as his professor. Wakefield, who earned 200 victories as a knuckleballer, is a special-assignment instructor for the Red Sox, his team for 17 seasons. He said he knew immediately that Wright had a chance to succeed.

“He already knew how to take the spin off the ball,” Wakefield said. “That’s one thing that I can’t teach: the ability, or the feel, to consistently take the spin off. Once I realized he could do that, then it was just tweaking his mechanics a little bit to be more consistent in the strike zone.”

Wright reached the majors in 2013, his first of three seasons bouncing between Boston and the minors. He has established himself now but still speaks often with Wakefield, who calls some Red Sox games on the New England Sports Network and makes sure to watch all of Wright’s starts.

“The biggest thing we worked on was learning why the ball does what it does and correcting your misfires within a couple of pitches,” Wakefield said. “Like if you throw one up and in to a righty or yank one down and away from a righty, then what mechanical flaw just happened to cause you to do that? You need to fix it right away from pitch to pitch, or within a couple of pitches, and he’s been able to do that.”

Wright found out ahead of time that he had made the All-Star team, and he called Wakefield to share the news before the announcement. Wakefield made just one All-Star team, in 2009, when he was 42. His role was to pitch in extra innings or a blowout, but the AL won by one run, and Wakefield did not appear.

Knuckleballers at the All-Star Game are fairly rare. R.A. Dickey pitched an inning in 2012; Charlie Hough pitched an inning and two-thirds in 1986; and the Hall of Famer Phil Niekro, a five-time All-Star, faced just four batters overall. But Wright’s success carries on a proud legacy.

“I don’t think the pitch will ever die,” Wakefield said. “It may disappear for a while, but I don’t think it’ll ever go away for good. I mean, it’s been around for 100 years or so. It’s a very valuable asset to any club that has patience. That’s the hard part — finding a club that has the patience.”

The Red Sox were that team in 2012, and their patience has been rewarded.