For weeks after the vote, the abuse kept coming: Venomous, sexist phone calls and emails, venting rage at the five women on Seattle’s City Council who outvoted four men to derail a sports arena project.

“Disgraceful hag” was one of the milder messages. “Go home and climb in the oven,” one councilor was told.

This unfolded not in 1966, during an era when American women mobilized en masse to demand equality, but 50 years later in May of 2016 — two months before the first woman was nominated to lead a major party’s presidential ticket.

It’s a complicated time for gender relations in the U.S., as the campaign pitting Hillary Clinton against Donald Trump has underscored — most recently, with the fallout from their first debate and a sharp exchange about Trump’s attention to a former Miss Universe and her weight.

On one hand there’s been great progress toward equality. Women hold the top jobs at IBM and General Motors, for example. They were recently approved to serve in all military combat jobs, and it’s possible, depending on the election outcome, that troops could soon be saluting the first female commander in chief.

At the same time, deep and obvious gaps remain. Consider this year’s reboot of “Ghostbusters,” with women replacing the male leads of the original. Misogynistic comments circulated on social media demanding the film’s stars appear nude or be “hot.”

Or the way some sports commentators belittled women’s accomplishments at the Rio Olympics.

Or the backlash in, of all places, progressive Seattle, after the five female councilors voted against the proposed sale of a street to help make way for a new arena that could host an NBA team. One local attorney, in a signed email to all five women, said, “I can only hope that you each find ways to quickly and painfully end yourselves.”

Council member Lorena Gonzalez, a lawyer who has represented victims of sexual abuse, said the controversy “hit a nerve” because it coincided with a presidential campaign that has exacerbated gender tensions.

In many male-dominated domains, women’s strides have been slow-paced and, even then, greeted with resentment.

“Cultural change often comes with some backlash,” said Emily Martin, the National Women’s Law Center’s general counsel. “Some people feel threatened by women’s progress.”

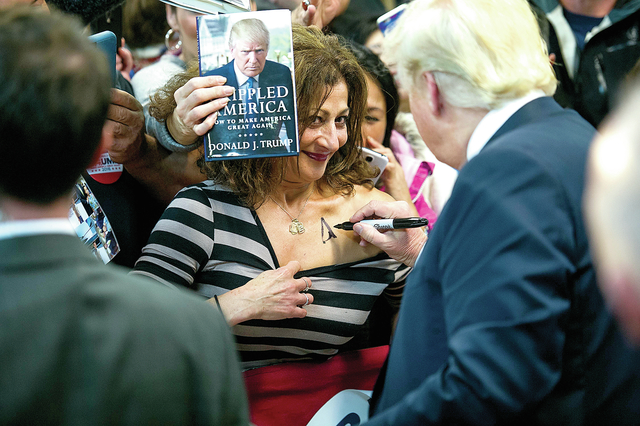

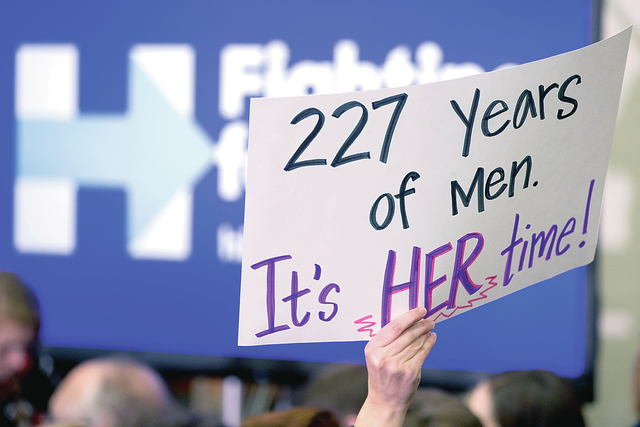

That culture clash has become striking in this election year. As feminists celebrated Clinton’s glass-shattering nomination with the slogan “I’m With Her,” Trump claimed the only thing Clinton had going for her was “the woman’s card.” Some of his supporters wear “Trump that B—-” T-shirts.

Polls show Clinton, a Democrat, benefiting from a gender gap that’s been a fact of American politics since 1980, with women voting for her party more reliably than men in each presidential election. This year’s gap could be the biggest ever; a New York Times poll in mid-September showed Trump, a Republican, leading among likely male voters by 11 percentage points, while Clinton led among likely female voters by 13 points.

Brooke Ackerly, a political science professor at Vanderbilt, said the sexist sentiments on display during the campaign aren’t new to American politics, but are louder and more visible.

“It suggests to me there’s some latent anger that’s being given permission to express itself,” said Ackerly, depicting Trump as the catalyst for this. “What’s new is that we’re seeing it in public.”

Clinton, of course, has been targeted by sexist taunts for many years, and says she takes them in stride.

Still, said Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, “I’m concerned about what it means for younger women who see this as what you might confront if you dare to tread on what is seen as male turf.”

Indeed, elective politics remains predominantly male turf. Women comprise more than half the U.S. population, yet account for just a fifth of all members of Congress and one-fourth of state lawmakers, according to a recent survey. And that’s a better showing than for women in such fields as construction and video-game design.

For two years, software engineer Brianna Wu of Boston has been a target of the online harassment campaign known as Gamergate, which subjected several women in the video-game industry to misogynistic threats.

“It’s still a constant drumbeat,” said Wu, who became a target after ridiculing those who decried women’s advances in the male-dominated industry.

Unsurprisingly, Clinton is backed by the National Organization for Women and Planned Parenthood. Trump’s supporters include leaders of national anti-abortion groups.

Some prospective voters don’t fit easily into the obvious boxes. There are conservative women who disdain Clinton, yet find Trump’s rhetoric and behavior repugnant. There are men planning to vote for Clinton who wish she would be more outspoken about challenges facing boys and fathers.

One of those men is author Warren Farrell of Mill Valley, California, a figure in what’s loosely known as “the men’s movement.”

“I’m supporting Hillary Clinton despite the people in her campaign who are less compassionate toward men, less understanding of the importance of fathers,” said Farrell. As for Trump, “he represents everything that women fear about men — blustery, grandiose, narcissistic,” Farrell said.

Trump has many enthusiastic female supporters, including Amber Smith, who served in Iraq and Afghanistan as an Army helicopter pilot.

Smith says Trump “has a backbone” and perceives Clinton as seeking to portray women as victims.

“We live in a country that provides equal opportunities for men and woman,” Smith said. “I wanted to be an air mission commander based on my own merits and skill level, not because of my gender.”