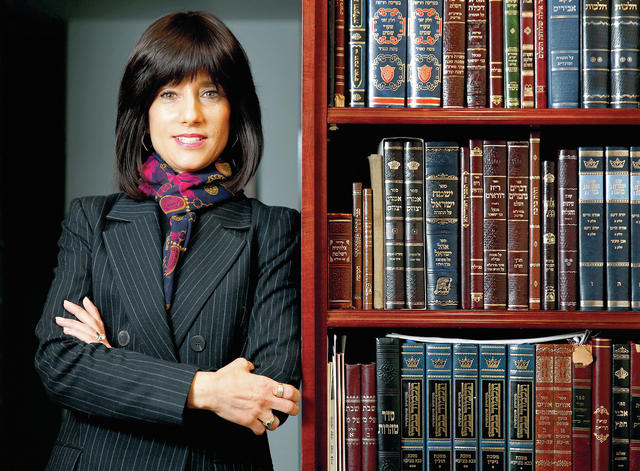

NEW YORK — In some ways, Rachel Freier has a background that might be expected in a new civil court judge. She is a real estate lawyer who volunteers in family court and in her community, where she even serves

NEW YORK — In some ways, Rachel Freier has a background that might be expected in a new civil court judge. She is a real estate lawyer who volunteers in family court and in her community, where she even serves as a paramedic.

But Freier starts work Tuesday as something quite unexpected. She’s believed to be the first woman from Judaism’s ultra-Orthodox Hasidic community to be elected as a judge in the United States.

A proud product of a world with strict customs concerning gender roles and modesty, the new Brooklyn civil court judge started college as a married, 30-year-old mother of three children and had three more before graduating. A pathbreaker who embraces tradition, she has sometimes had to explain herself to both outsiders and fellow believers.

“My commitment to the public and my commitment to my religion and my community — the two can go hand in hand,” she says.

At a swearing-in ceremony last month, she both vowed to uphold the Constitution and pledged to illuminate the Hasidic world for her new colleagues.

“This is a dream,” she told the gathering. “It’s the American dream.”

There’s no official tally of American judges’ religions, but experts aren’t aware of any Hasidic woman before Freier winning a judicial post. It is extremely rare even in Israel for Hasidic or other ultra-Orthodox women to hold any elected position.

Freier, a political newcomer whose uncle is a former judge, won a three-way Democratic primary and the general election in a swath of Brooklyn that includes the heavily Hasidic Borough Park neighborhood.

Her election is “a step for the ultra-Orthodox community at large,” showing it’s open to women making progress on the political ladder, said Yossi Gestetner, a longtime Hasidic political activist and public relations consultant who co-managed Freier’s campaign.

Hasids and other ultra-Orthodox groups together make up only 6 percent of America’s estimated 5.3 million adult Jews, according to a 2013 Pew Research Center study.

Dating to 18th-century Eastern Europe, Hasidism combines stringent adherence to Jewish law and a joyful belief in mysticism. Followers often speak Yiddish, wear traditional dress including beards and sidelocks for men and wigs for married women, and separate men and women in contexts ranging from buses to classrooms.

“The very idea that an ultra-Orthodox woman could be a judge” is notable, said Samuel Heilman, a City University of New York sociology professor who studies Orthodox Judaism. Under the strictest interpretations of Jewish law, women can’t be judges or largely even witnesses in the rabbinical courts that weigh various disputes in Orthodox communities. (Freier notes that her new post is separate from those tribunals.)

Freier, 51, nicknamed Ruchie, started working as a legal secretary after high school. College wasn’t customary for Hasidic women, though it has since become more common.

But when her husband, David, got a college degree, she aspired to one of her own. After graduating from a women-only, Orthodox Jewish-friendly program at private Touro College, she went on to Brooklyn Law School, finishing in 2005.

Some other Hasidic Jews questioned what she was doing. But they came to realize “I was completely devoted to our religion and our tradition, and this was something I wanted to do regardless,” she says.

“I didn’t want to ever be considered someone who was turning away from my community,” but rather to work within its structure, she said.

That has sometimes required finding creative ways to resolve issues.

An appeal for help from boys who had chafed in Orthodox Jewish schools, for example, led Freier to found a program that helps young men get general-equivalency diplomas.

Then Freier was enlisted to represent Orthodox Jewish women who wanted to join an all-male volunteer ambulance corps, aiming to aid fellow women during childbirth or gynecological emergencies.

After ambulance corps leaders rebuffed the idea, which a well-known Orthodox Jewish blog called a “new radical feminist agenda,” Freier helped the women launch their own volunteer service and joined it herself. She was still taking her turn on call this past week.

If there’s a message she hopes her election sends, it’s “don’t give up.”

“And don’t let go of your standards.”