DENVER — Tuesday marks 50 years since a groundbreaking Colorado law significantly loosened tight restrictions on legal abortions. ADVERTISING DENVER — Tuesday marks 50 years since a groundbreaking Colorado law significantly loosened tight restrictions on legal abortions. Before the law,

DENVER — Tuesday marks 50 years since a groundbreaking Colorado law significantly loosened tight restrictions on legal abortions.

Before the law, Colorado — like many states — allowed abortions only if a woman’s life was at stake.

In 1967, a Democratic freshman state lawmaker introduced a bill that allowed abortions if the woman’s physical or mental health was threatened, if the unborn child might have birth defects or in cases of rape or incest.

Rep. Richard Lamm said he feared he might be committing political suicide by introducing the bill to the overwhelmingly male, Republican-dominated Legislature.

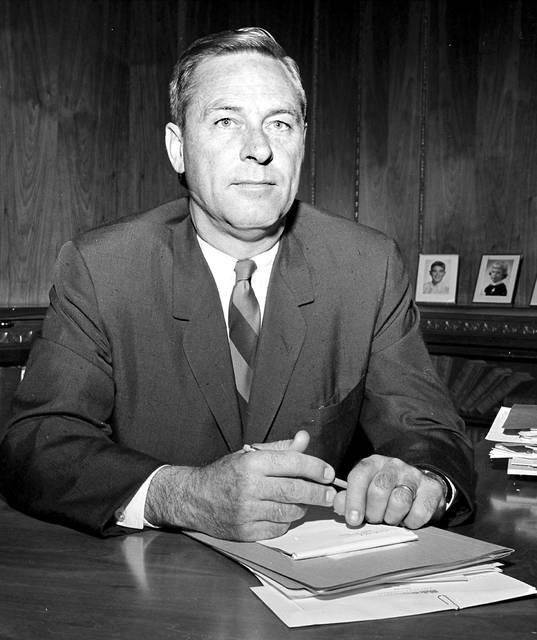

But within weeks, Republican Gov. John Love signed the bill into law, making Colorado the first state to loosen restrictions on abortion — six years before the U.S. Supreme Court would legalize it nationally.

“I was pushing on a half-open door. It gave way so much more easily than I ever dreamed it would,” recalled Lamm, now 81, in an interview with The Associated Press.

But all abortions still had to be approved by three-doctor panels at participating hospitals and were only permitted during the first 16 weeks of pregnancy.

Instead of ending his newfound political career, Lamm went on to serve three terms as the state’s governor. He is currently the co-director of the University of Denver’s Institute of Public Policy Studies.

Lamm said recently that when he introduced the legislation, the women’s movement was just starting to take off and the concept that citizens should have more personal freedom was becoming more important in society.

At the time, abortion was not one of the Colorado Republican Party’s most pressing issues and there was no organized opposition in the state to abortion rights because the idea was so new, Lamm said.

Key to Lamm’s effort was ally Ruth Steel, an activist who had lobbied lawmakers in 1965 to allow public health officials to discuss and to provide birth control with residents. She worked closely with John Bermingham, a Republican state senator who is now 93 and retired, to shepherd the contraception bill though the Legislature.

While on lobbying trips to the Capitol, Steel dressed formally, wearing a hat and gloves, but had no qualms talking to lawmakers frankly about issues related to sex, Lamm said.

A woman in charge of proofreading bills in the basement of the Capitol was essential to advancing the bill through the Legislature, Bermingham said in an interview.

Bermingham learned that she supported the bill, and he asked her to wait until a Senate leader who opposed it would be away so the bill could be introduced without being assigned to a committee seen as sure to kill it.

While the bill was under debate, a woman denied an abortion at Denver’s public hospital shot herself in the abdomen and survived. The fetus did not survive. The doctor who treated the woman testified on the bill, Bermingham said.

After the Legislature approved the measure, opponents picketed outside the governor’s mansion.

Love, a Republican who died in 2002, said at the time that he struggled with what to do with the bill. He said he was conflicted over whether abortion would be used as an alternative to birth control.

In the era of divisive and turbulent social and political change, he said his mail was about evenly divided between supporters and opponents.

Love ultimately decided to sign the bill to keep government out of what he viewed as a personal decision, said his son, Dan Love. The elder Love was re-elected in 1970.

Eleven other states followed suit. And four more lifted all abortion restrictions — New York, Washington, Hawaii and Alaska — before 1970. The 1973 Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision legalized abortion nationwide.

In Colorado, opponents had feared the state would become “an abortion mecca” for women seeking to end their pregnancies. That did not happen, partly because women who wanted abortions had to appear before a hospital panel and could not simply show up and get them.

There were only 10 abortions reported to the state health department in 1966. Between the law’s signing in April and the end of 1967, 120 abortions were reported. The patients ranged from a 12-year-old girl who had been raped to a 48-year-old woman. About a quarter were from outside Colorado.

Most were performed based on psychiatric grounds or therapeutic reasons with no additional specifics provided.