WASHINGTON — Remember the Republican health care bill? ADVERTISING WASHINGTON — Remember the Republican health care bill? Washington is fixated on President Donald Trump’s firing of FBI chief James Comey and burgeoning investigations into possible connections between Trump’s presidential campaign

WASHINGTON — Remember the Republican health care bill?

Washington is fixated on President Donald Trump’s firing of FBI chief James Comey and burgeoning investigations into possible connections between Trump’s presidential campaign and Russia.

But in closed-door meetings, Senate Republicans are trying to write legislation dismantling President Barack Obama’s health care law. They would substitute their own tax credits, ease coverage requirements and cut the federal-state Medicaid program for the poor and disabled that Obama enlarged.

The House passed its version this month, but not without difficulty, and now Republicans who run the Senate are finding hurdles, too.

A look at some of those obstacles and what senators are trying to doing about them:

Short-term fix?

GOP senators say they’re discussing a possible short-term bill if their health care talks drag on. It might include money to help stabilize shaky insurance markets with subsidies to reduce out-of-pocket costs for low-earning people and letting states offer skimpier, and therefore less expensive, policies.

It’s unclear Democrats would offer their needed cooperation, but Republicans are talking about it.

“We’ve discussed quite a bit the possibility of a two-step process,” said Sen. Lamar Alexander, chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee. “In 2018 and ’19, we’d basically be a rescue team to make sure people can buy insurance.”

That could mean Republicans might even temporarily extend Obama’s individual mandate — the requirement that people buy coverage or face tax penalties. It’s perhaps the part of Obama’s law that Republicans most detest. But it does prompt some people to purchase insurance, which helps curb premiums and make markets viable.

Alexander, R-Tenn., said there’s a “strong bias” to address short- and long-term problems in a single bill.

“If we can’t do the real thing, we’d have to do the next best thing,” Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, said of short-term legislation.

Time is ticking

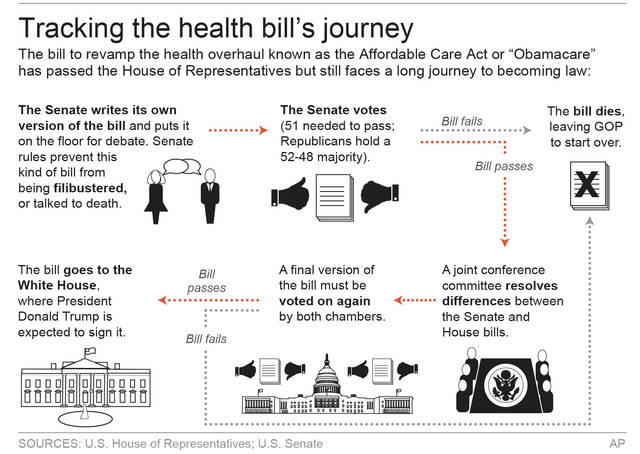

Because Democrats oppose the repeal effort unanimously, Republicans will need 50 of their 52 senators to back their overhaul so Vice President Mike Pence’s tie-breaking vote would clinch passage. GOP senators show no signs of producing a bill soon.

Time is important, especially with Trump’s problems distracting lawmakers. Insurance companies could grow increasingly spooked by the uncertainty and make health care markets even worse by raising premiums or pulling out.

Also, the longer it takes Republicans to write the legislation, the less time they’ll have for tax cuts and other GOP priorities.

GOP divisions

The House version would end in 2020 the extra federal payments that states get under Obama’s law for expanding Medicaid to additional people. Senate conservatives prefer to start phasing out that money next year. But 20 GOP senators come from states that expanded Medicaid and want to protect those voters, so many would rather reduce the payments over many years.

Conservatives and moderates are also bickering over how tightly to cut future spending on the entire Medicaid program.

Many Republicans want to refocus the House’s health care tax credits, which grow with people’s ages, by boosting subsidies for lower earners. Eager to reduce premiums, many want to roll back Obama mandates such as requiring insurers to cover specified services, including substance abuse counseling, but there are questions about how far to go.

Decisions await on helping states subsidize people with costly medical conditions and keeping insurers from fleeing unprofitable markets.

Making Medicaid, the tax credits and other programs more generous than the House will cost many billions of dollars. Senators will need ways to pay for that.