Researchers can now look with a bird’s-eye view at rapid ohia death in an entire forest and also microscopically within a single tree.

Collaborating researchers showcased their wide-ranging technology for journalists Monday at the Hilo Air Patrol.

A tree can be infected with either of the two species of Ceratocystis fungi that causes ROD for months before symptoms of the illness — browning leaves — appear, but once symptoms do show up the tree dies within weeks. An estimated 75,000 acres of ohia forest on the Big Island have already been affected. More than 200,000 ohia trees died between 2015 and 2016, with some research estimates placing the number closer to 300,000.

Ohia are “perhaps one of the most important native Hawaiian trees,” according to the University of Hawaii at Manoa College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources. That’s because ohia are among the first plants to take root in freshly cooled lava “and are therefore instrumental in the process of soil development and ecological succession.”

But researchers have struggled to learn how the disease typically spreads from tree to tree and forest to forest.

Now, researchers from the state Department of Land and Natural Resources, the U.S. Geological Survey, the University of Hawaii at Hilo and the Carnegie Institute for Science are partnering to do unmanned drone photography to observe changes in individual trees, traditional lab testing, “suitcase” mobile laboratory ROD confirmation in remote locations and airborne observatory monitoring of whole-forest health.

Rapid ohia death infects and blocks water from moving through a tree’s vascular tissue. When the fungus interrupts the flow, water cannot get to the branches and leaves. Without a water supply, sugar and other nutrients can’t be delivered from the leaves to the rest of the tree and it dies.

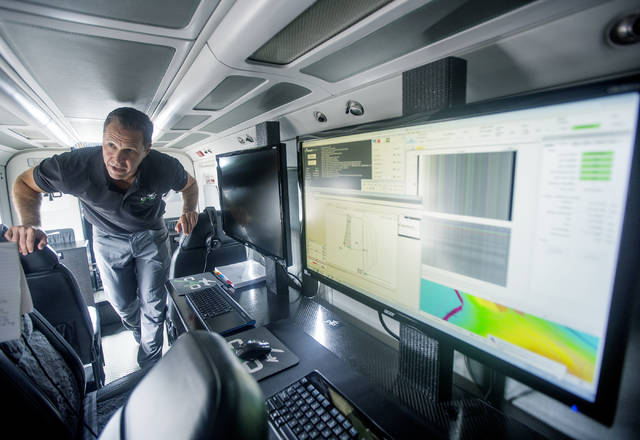

Professor Greg Asner, director of the Carnegie Airborne Observatory, flies with a team of researchers aboard an approximately $15 million grant-funded aircraft. The first Big Island forest-wide flights were taken in January 2016.

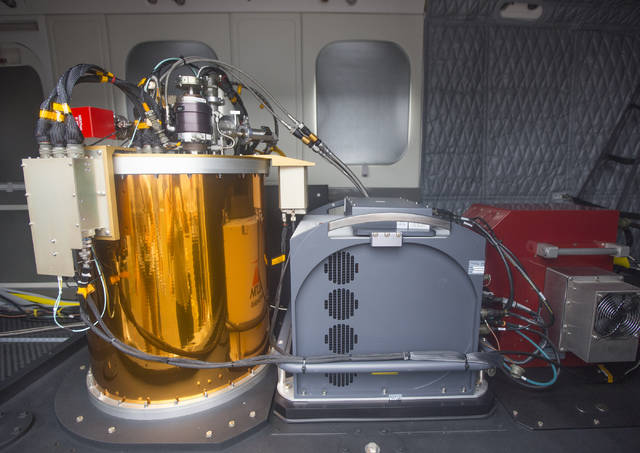

The Airborne Observatory contains a wide range of high-tech equipment.

That equipment includes a laser system for 3-D images to differentiate rocks and soil from living matter such as ohia trees; a spectrometer to measure colors to see if leaves are green and healthy, gray and dead from ROD or somewhere in between; and computer systems capable of storing up to two terabytes of information per flight.

Asner said the spectrometer reveals intricate details within the tree canopy. When combined with information learned on the ground and from drone flights, scientists are beginning to get an expanded view of the impact of ROD.

“Work gets done minute by minute while we’re up in the air,” Asner said.

On a clear day, Devon Woodword of Canada, one of the observatory’s pilots, said two flights can happen, each lasting about four to six hours.

Researchers want to know how rapidly ROD is spreading around the Big Island, the only island affected in the state. Half or more of the trees in Hawaii’s forests statewide are ohia, making their potential loss a critical factor for the state’s ecosystem.

Ryan Perroy, associate professor in the Department of Geography and Environmental Science at UH-Hilo, said his team’s goal is to get “very, very fine resolution” images with drones and then “to see what we can learn about the spread of the disease.”

The drones have now been used to repeatedly fly over specific forest areas, where individual trees in the process of dying from ROD were mapped. Monthly drone flights are helping researchers better understand the true speed of ROD’s spread when individual trees are observed throughout the dying process. And annual Airborne Observatory flights help keep track of overall forest health.

Researchers hope to learn how to treat ROD, how to prevent it and how to slow or prevent its spread.

Perroy said researchers can study why particular trees stand up to ROD longer than others. Are they resistant? Are they shorter, meaning wind doesn’t knock them down as fast?

The team is hopeful to answer those questions — and many others.

Email Jeff Hansel at jhansel@hawaiitribune-herald.com.