When Pele moves into town, all you can do is get out of the way.

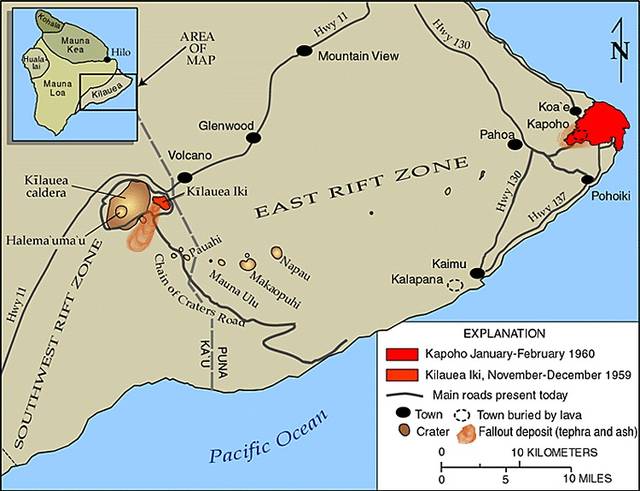

That’s a lesson Frances Kakugawa recalled learning when another volcanic eruption from Kilauea destroyed her town of Kapoho in 1960.

But it’s one she’s afraid a few people are forgetting as lava inundates the subdivisions of Vacationland and Kapoho Beach Lots, located south of the former plantation community she grew up in.

Four people were evacuated by helicopter Sunday after lava closed off access routes.

“I’m thinking, ‘Hey, come on, why don’t you listen?’” she said to herself after hearing reports of people being airlifted after choosing to stay.

“That has been bothering me. I feel for the residents, and I know what it’s like.”

Kakugawa, 82, is the author of “Kapoho: Memoir of a Modern Pompeii,” which describes her childhood in Kapoho and the eruption that ultimately buried the town under a blanket of lava.

It’s a scene that’s been playing out in that part of Puna again since May 3, when numerous fissures began creating fiery rivers of molten rock that now stretch for miles from Leilani Estates to Kapoho.

Back when she lived there, Kapoho didn’t have electricity, and only a theater that played black-and-white movies was run by a generator, Kakugawa recalled. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the town was home to about 300 people.

“We all knew each other,” Kakugawa said. “We never locked our houses. We left keys in the car.”

Similar to the current eruption of Kilauea, the 1960 eruption was preceded by numerous earthquakes that split the ground apart, including underneath her family’s home, which was moved to Pahoa before lava could cover it. Relocating was a blessing in a way since the family could finally have electricity.

According to the USGS’ Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, tiny earthquakes were recorded in Pahoa the last week of 1959, shortly after the eruption at Kilauea Iki in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park ended. The quakes moved down the rift zone toward Kapoho.

By daybreak Jan. 13, 1960, Kapoho was severely cracked along a fault, and ruptures caused loud booms, prompting evacuations. The eruption began that night and didn’t stop until Feb. 19.

In addition to destroying the village, the eruption covered warm springs and extended the coast by 100 yards.

There were warning signs before the ground began to shake, Kakugawa recalled.

“When we were growing up, we had underneath our house a sulfuric smell sometimes,” she said, which caused her father’s fishing nets to rot.

Her father’s relationship with Pele extended beyond that.

Kakugawa said he would sometimes see an old woman with long white hair and no feet behind him on the rocks when he went fishing along the coast at night. He saw that woman as the volcano goddess and thought she was warning him that the waves were too rough and dangerous.

“He would bow to her and say, ‘Thank you, Pele,” Kakugawa said. “He would grab the netting and walk home.

“I’ve heard people say that their grandpa had that experience. … Pele was very real in our life, and I think she still is.”

Email Tom Callis at tcallis@hawaiitribune-herald.com.