Andy Warhol exhibit includes old favorites, new insights

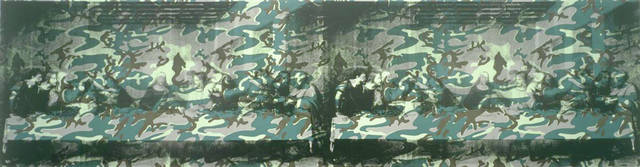

This image released by the Whitney Museum of American Art shows “Camouflage Last Supper,” a silkscreen ink and acrylic on canvas painted by Andy Warhol in 1986. The painting, which is over 25 feet long, is part of an exhibition titled “Andy Warhol - From A to B and Back Again,” running through March 31 at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. (Andy Warhol/Whitney Museum of American Art via AP)

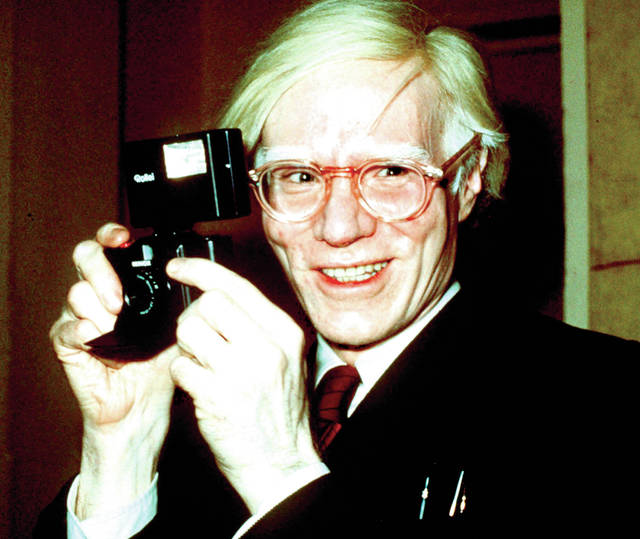

FILE - In this 1976 file photo, pop artist Andy Warhol holds a camera in New York. A new exhibition titled, “Andy Warhol - From A to B and Back Again,” is running through March 31 at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. (AP Photo/Richard Drew, File)

NEW YORK — The 25-foot long “Camouflage Last Supper,” one of Andy Warhol’s last and most personal works, floods a full wall of a room on the fifth floor of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

NEW YORK — The 25-foot long “Camouflage Last Supper,” one of Andy Warhol’s last and most personal works, floods a full wall of a room on the fifth floor of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The massive acrylic and silkscreen mural captures the artist’s seemingly contradictory piety and irreverence. It’s one of more than 350 works on display in the largest retrospective of Warhol’s prolific career in nearly 30 years.

ADVERTISING

While Warhol’s style has remained ubiquitous since his death in 1987, even the most devout pop-art connoisseurs can learn much from “Andy Warhol — From A to B and Back Again.” It includes famous works as well as material on view for the first time. Newly revealed information about the painfully private artist’s life adds new dimensions to our understanding of him and his work.

“There is something in his work that speaks to our contemporary culture,” said Donna De Salvo, the Whitney’s deputy director for international initiatives and senior curator, who organized the exhibition with Christie Mitchell and Mark Loiacono. “There is punch in Warhol’s work, there’s mystery, and it’s not easy to know what’s going on.”

“Camouflage Last Supper” combines an amplified photo print of Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic 15th-century mural with a green-and-brown camouflage pattern from a fabric swatch. Created in 1986 amid the AIDS crisis that devastated the New York City gay community and art world, “Camouflage Last Supper” lays bare the artist’s conflicted emotions as a gay man and a Byzantine Catholic.

Warhol’s deep faith was little-known outside of his tight-knit religious community. His parents were Ruthenians, born in a village in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains, at the northern border of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

On one hand, Warhol was a fixture at downtown Manhattan’s hottest nightclubs, flanked by glamorous models, actors, rock stars and drag queens. The same man visited the Church of St. Vincent Ferrer on the Upper East Side nearly daily. He would hide in the back of the church on Sundays for fear of being outed, and often slipped out before Holy Communion to retain his ghostlike presence. He slept near a crucifix shrine, wore a cross under his trademark black turtlenecks, and carried a rosary in his pocket.

Warhol’s career start as a commercial illustrator of women’s footwear quickly evolved as he garnered attention for his flamboyance and representations of American commercialism, such as his famous depictions of Campbell’s Soup cans and portraits of celebrities and world leaders. The Warhol art that everyone knows encompasses the fifth floor of the Whitney, including “Green Coca-Cola Bottles,” Brillo Box sculptures, and self-portraits, with a multi-room gallery installation of his colorful silk-screened flowers imposed on shocking pink cows.

The repetition of design and mixed cultural images in Warhol’s art feels familiar in a digital age, which he arguably anticipated and foreshadowed.

Along with his hidden faith, Warhol’s philanthropic side was overshadowed by his reputation as a proponent of Business Art. The real Warhol transcended and subverted his fortune and sweeping fame. He provided funding for a soup kitchen operated by the (Episcopal) Church of the Heavenly Rest on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, and volunteered there. He paid seminary tuition for a nephew who wanted to become a priest.

One of Warhol’s most important collaborators was Jean-Michael Basquiat, with whom he began working in the 1980s. Basquiat died of a drug overdose in 1988 at age 27, about a year and a half after Warhol died at age 58 of a sudden, postoperative arrhythmia. While their time together was short, it produced hundreds of powerful works. On view side-by-side at the Whitney are Basquiat’s and Warhol’s acrylic-on-canvas collaborations “Paramount” (1984-85) and “Third Eye” (1985), both on loan from a private collector. “Paramount” embodies both artists’ absorption in capitalism, politics and celebrity.

Also from a private collection, Warhol’s “Superman” (1961) is a harsh critique of the machismo of Abstract Expressionist “action” painting; it offers a suggestively queer version of the superhero.

Besides the artworks (which include some of Warhol’s films), the exhibition also includes ephemera and scholarship that uncovers new intricacies about the artist we think we understand, while launching a Warhol for the 21st century.

“For me, the most potent stuff is the later work,” De Salvo says. “Some of it is mystifying, but it’s still asking us questions. It feels as though it makes Warhol a live issue again.”

“Andy Warhol — From A to B and Back Again” runs through March 31, 2019, at the Whitney Museum of American Art. It travels to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (May 18-Sept. 2,) and the Art Institute of Chicago (Oct. 20, 2019-Jan. 26, 2020). Tickets are available online.

___

Online: https://visit.whitney.org/ga/ticketing.aspx?node_id=540044&location=navbar#/step