M5.5 quake: A bump in the night toward more typical seismic background

Early Wednesday morning, just before 1 a.m. on March 13, houses in east Hawaii began to shake. Without a doubt, it was an earthquake. To those who endured the near-daily shaking from last summers collapse events at Kilaueas summit, this weeks earthquake was clearly different.

Early Wednesday morning, just before 1 a.m. on March 13, houses in east Hawaii began to shake. Without a doubt, it was an earthquake. To those who endured the near-daily shaking from last summer’s collapse events at Kilauea’s summit, this week’s earthquake was clearly different.

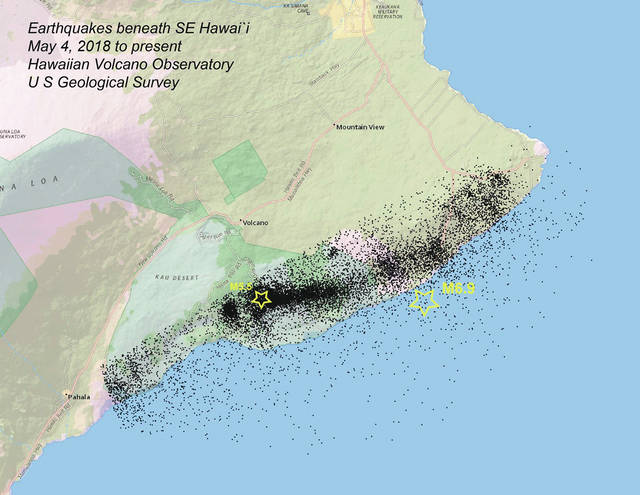

Geophysicists from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) quickly verified that the earthquake did not originate from beneath Kilauea Volcano’s summit region. Rather, the earthquake was centered 12 km (roughly 7 miles) south-southeast of Volcano Village, at a depth of 7 km (~4 miles) below sea-level. HVO reported the earthquake’s magnitude as M5.5.

ADVERTISING

Earthquakes at this location and depth in Hawaii are due to movement along a decollement or detachment fault which separates the top of the original oceanic crust from the pile of volcanic rock that has built up to form the Island of Hawaii. This is the same fault that was responsible for last May’s M6.9 earthquake.

The first earthquake in Hawaii that scientists associated with decollement faulting was arguably the M7.7 earthquake in November 1975, Hawaii’s largest earthquake in the past century. The great Ka‘u earthquake beneath Mauna Loa’s southeast flank in 1868 has also been interpreted as a result of decollement faulting. This is in part because the decollement is the only fault large enough to produce such a high-magnitude earthquake.

Wednesday’s M5.5 earthquake is, to date, the largest event among the thousands of earthquakes considered aftershocks of last May’s M6.9. The aftershock sequence following the 1975 earthquake lasted roughly a decade, and it is generally understood that aftershock sequences could include earthquakes as large as one magnitude unit lower than the mainshock magnitude.

In this regard, while not strictly predictable, this M5.5 was expected. And, we expect aftershocks to persist for several more years.

Importantly, though, this week’s earthquake does not signal an increase in volcanic activity. Instead, it is part of an evolution of Kilauea seismicity back to more typical levels.

HVO’s seismographic network has expanded and improved since 1975. Studies of the 2018 M6.9 earthquake show the extent of earthquake fault movement to underlie a large portion of the island’s southeast coast. This is quite similar to the model computed for the 1975 earthquake developed with more limited observations.

Besides scientific interest in understanding how faults move during earthquakes, these models of fault rupture factor into considerations of possible tsunami generation and other earthquake impacts.

The timing of the events in 2018 – the draining of Pu‘u O‘o on April 30, the migration of earthquakes from Pu‘u ‘O‘o to Kilauea’s lower East Rift Zone and breakout of lava in Leilani Estates on May 3, the M6.9 earthquake on May 4 and subsequent collapse of the floor of Kilauea Caldera – suggests connections between and among these processes. Much of HVO’s work now is focused on describing these connections to much greater detail. As one of our colleagues wrote several months ago, our ultimate challenge is to understand what Kilauea will do next (https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/observatories/hvo/hvo_volcano_watch.html?vwid=1393).

For example, further seismological modeling offers insights into how the M6.9 earthquake rupture progressed in time and space along the decollement. This relates to redistribution of stresses beneath Kilauea’s southeast flank due to the earthquake. The impacts of these stress changes on the rift zone and how magma was supplied to lower East Rift Zone eruption of 2018 remain to be studied.

Because of the overwhelming numbers of earthquakes recorded between April and August 2018, much of the continuing aftershock sequence awaits detailed review and analysis. As with any earthquake, the locations and the timing of the earthquakes will provide our first clues of why they happened. They will also help us piece together other important details of Kilauea’s awesome 2018 sequence.

Kilauea Activity Update

Kilauea is not erupting. Rates of seismicity, deformation, and gas release have not changed significantly over the past week.

Deformation signals are consistent with refilling of Kilauea Volcano’s deep East Rift Zone (ERZ) magma reservoir. Sulfur dioxide emission rates on the ERZ and at Kilauea’s summit remain low.

Hazards still exist at the lower ERZ and summit of Kilauea. Residents and visitors near the 2018 fissures, lava flows, and summit collapse area should heed Hawaii County Civil Defense and Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park closures and warnings. HVO continues to closely monitor Kilauea for any sign of increased activity.

The USGS Volcano Alert level for Mauna Loa remains at NORMAL.

Island-wide, there was one earthquake with 3 or more felt reports during the past week. On March 13 at 12:55 a.m. HST, a magnitude-5.5 earthquake occurred 12 km (7 mi) SSE of Volcano at 7 km (4 mi) depth. For more information on this event, see https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/hv70863117#dyfi .

For more information, visit the HVO website (http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov) for past Volcano Watch articles, Kilauea daily eruption updates and other volcano status reports, current volcano photos, recent earthquakes, and more; call (808) 967-8862 for a recorded Kilauea summary update; email questions to askHVO@usgs.gov.

Volcano Watch (http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/) is a weekly article and activity update written by scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey‘s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.