Wright On: AJA baseball rich in tradition, memories

The old-timers tell the history of baseball in and around Hilo in a way younger folk might think it was a distant place, far, far away.

The old-timers tell the history of baseball in and around Hilo in a way younger folk might think it was a distant place, far, far away.

History though, teaches a different story when it lives on as it will this week in the form of the Hawaii State Americans of Japanese Ancestry Baseball Tournament.

ADVERTISING

Baseball has forever been popular on the Big Island, but the community structures they knew back before World War II, the leagues, ballparks, the games themselves, are mostly all gone, if not forgotten.

“We had so many different ethic groups and they all wanted to play baseball,” said Royden Okunami, president of the Hawaii entrant in the four-island AJA baseball league. “Every (sugar) plantation had their own team, with everyone eligible, no matter where you came from, but then they also had a Chinese team, Filipino and Portuguese teams, and, of course the Japanese team.”

Okunami said the 100th Battalion League, named in honor of the Hawaii-born Japanese-American men who volunteered to fight for America when they faced bigotry against them and their families because of the attack on Pearl Harbor, changed its name to Americans of Japanese Ancestry following the war. The 100th Battalion was the most highly decorated American unit of its size in all of WWII, and they chose to take the sharper edge off their distinctive name following the war.

But their pride and love for baseball has never diminished, and it will be on display again Saturday and Sunday at Wong Stadium for the 84th annual state AJA Baseball Tournament.

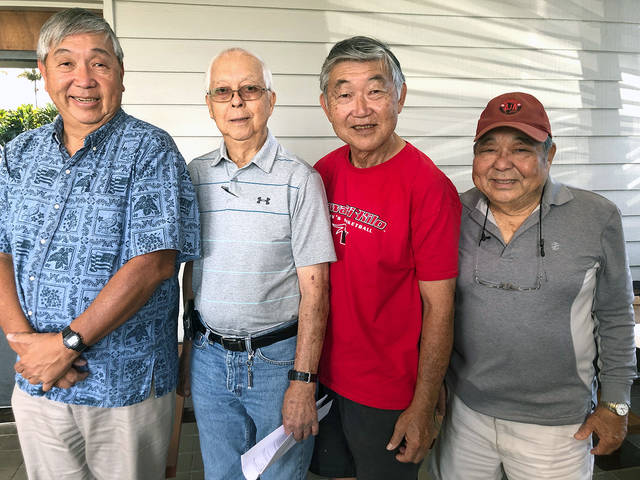

“All these things that occurred in the past, the plantation lifestyle, the laborers in the fields being the ballplayers, the way they formed the leagues so they could play, all these things we represent in a living memorial,” said Curtis Chong, one of the AJA administrators and the master of ceremonies for the dinners and awards gatherings surrounding the tournament. “We could have put up a monument, but instead, we have a living memorial, something that keeps building on itself, honoring the past in the present.”

Sadao Aoki grew up on the Hamakua Coast, playing plantation baseball, and recalls flatbed trucks with big stakes that would load up fans from one plantation and take them to the game somewhere against another plantation team.

“The games were exciting,” Aoki said, “and back then, the plantation teams never played the city teams in Hilo. Then, you add in the fact that some of the plantation teams would find a way to lure a top player by offering him a little more for his work, and that made it all a bigger deal.”

It was those home run hitters, the guys the other teams always tried to pitch around in the lineup, that added more spice to the teams and one of the best was Jimmy Miyake.

“He was a big deal,” Aoki said. “Jimmy was, to me, the All-American boy, without him it would just not have been the same. Every team feared him because he hit so many home runs.”

Miyake went from Hilo High School to the University of Hawaii where he played for Les Murakami. He pitched, played in the field, started a game against then-No. 1 ranked USC in Los Angeles (the Trojans ended up winning), then after his playing days he began coaching.

In that role, Miyake led the Hawaii team to the AJA state championship in 1990 and ’92, the latter being the last time a Big Island team won the tournament.

That last championship has proven difficult to repeat with the explosion of population on Oahu and the strict rule that each island has only one team.

Apart from his coaching success, when they recall Miyake, it always starts with his playing days.

“People who don’t know should know he is a true baseball somebody,” Chong said. “Whenever we played at Maui — I mean every single time we went there — we heard the same story all over again, ‘The longest home run ever hit at Hanapepe Field.’”

In college, on the plantation, in the AJA, they always tried not to pitch to Miyake, but he stood as close to the plate as they allowed so that the pitcher had to throw him something to hit if it was going to be a strike.

Miyake said he liked to play at Kauai the most — “That’s where I hit the most home runs,” — but he remembers all the talk when they visited Maui.

“I knew it was out,” he said of the long blast at Hanapepe, “I think the wind blew it.”

Others who were there didn’t think the alleged friendly wind had anything to do with it, but they were endlessly impressed by Miyake, who played AJA baseball until the age of 37.

“I was going to hang it up,” Miyake said, “but in 1986 we were all going to play at Rainbow Stadium, and I couldn’t resist, I wanted to play there one more time.”

He didn’t hit for the cycle that day, he didn’t hit the longest home run ever seen in the ballpark, but he brought some closure on his playing days and left plenty of conversations for baseball lovers to talk story about for decades to come.

“We’re all different here,” Chong said of the AJA administrators, “probably the only thing we all have in common is our love of baseball. It’s a major part of Japanese culture to give back and that’s what we’re trying to do. People like Jimmy give meaning to the stories, to everything we do, really, and it’s not just us who carry on the tradition.

“Everyone in Hilo has been supportive,” Chong said. “Our sponsors have been the best and they come from all parts of the community. We just want to keep the tradition alive.”

That last part brings us to the present where we can take in a game and see if we can spot another Jimmy Miyake out there, someone they’ll be talking about 40 years from now.

Send notes on teams and individuals that more people need to know about to barttribuneherald@gmail.com