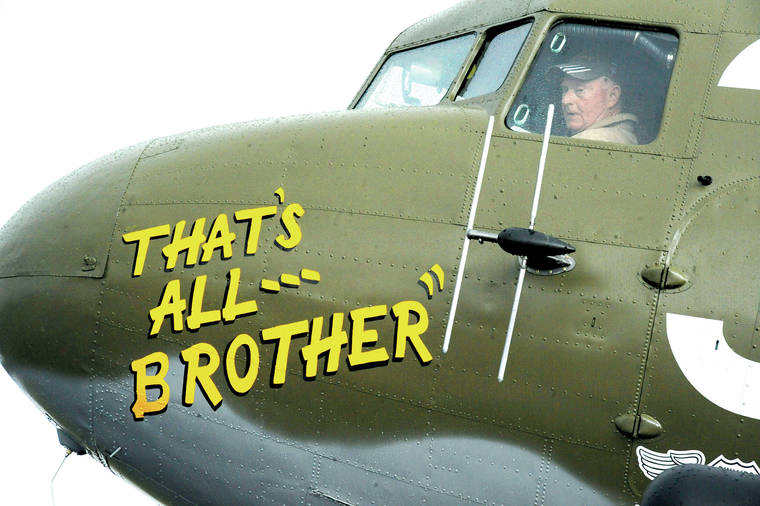

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. — Filled with paratroopers, a U.S. warplane lumbered down an English runway in 1944 to spearhead the World War II D-Day invasion with a message for Adolf Hitler painted in bright yellow across its nose: “That’s All, Brother.”

Seventy-five years later, in a confluence of history and luck, that plane is again bound for the French coast for what could be the last great commemoration of the Allied battle to include D-Day veterans, many of whom are now in their 90s.

Rescued from obscurity in Wisconsin after Air Force historians in Alabama realized its significance, the restored C-47 troop carrier that served as a lead aircraft of the main invasion force will join other vintage planes at 75th anniversary ceremonies in June.

After flying over the Statue of Liberty in New York on Saturday, the plane embarked for Europe with other vintage aircraft along the same route through Canada, Greenland and Iceland that U.S. aircraft traveled during the war. There, it and other flying military transports are expected to drop paratroop re-enactors along the French coast at Normandy.

“It’s going to be historic, emotional,” said pilot Tom Travis, who is helping fly That’s All, Brother to Europe for the event. “It’ll be the last big gathering.”

Air Force historian Matt Scales said there’s no question that the twin-engine plane is the same one that led the main D-Day invasion. It’s now operated today by the Texas-based Commemorative Air Force, which preserves military aircraft.

“There’s not a doubt in my mind. We have three separate documents that prove it,” said Scales, who found the aircraft with help of a colleague.

Scales tracked it down a few years ago while researching the late Lt. Col. John Donalson of Birmingham, who was credited with piloting the lead aircraft that dropped the main group of paratroopers along the French coast in preparation for the assault on June 6, 1944.

The night before infantry squads hit the beaches, Donalson’s aircraft and about 80 others were watched by news crews and military brass, including Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, as they took off, according to an official history by the 438th Troop Carrier Group. That’s All, Brother was at the tip of about 900 planes that made the flight across the English Channel to drop some 13,000 paratroopers in all.

Donalson’s plane was in the lead partly because it was equipped with an early form of radar that homed in on electronic beacons set up on the French coast by a small group of paratroopers in “pathfinder” aircraft, Scales said. Some mountings of that electronic system remain on the C-47’s fuselage.

Scales found wartime information about Donalson’s That’s All, Brother aircraft and matched records from both the military and the Federal Aviation Administration to determine the plane, manufactured by Douglas Aircraft Co. in 1944, still existed.

The aircraft was sold on the civilian market in 1945 and had changed hands several times before Scales found it. At one point, it was painted in a camouflage scheme similar to C-47s that flew during the Vietnam War.

“It had never crashed, it had never been damaged,” Scales said. “All the dozen owners who had it between the end of the war and when I found it had taken pretty good care of it.”

The aircraft was tracked down using identification numbers to a company in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, and purchased by the Commemorative Air Force in 2015 following a fundraiser that brought in some $250,000, Scales said. It was badly corroded and partially disassembled, but all the main parts were there.

With rebuilt piston engines, modern navigation and radio equipment and a fresh coat of paint, the reborn That’s All, Brother made its inaugural flight in February 2018. A crew now travels with it, offering flights to veterans and others.

The austere interior is lined with long metal benches for seats and the airframe is exposed for all to see. There’s no insulation, so the engines’ roar makes communication difficult when the props are spinning. A cable used to deploy paratroopers’ chutes runs along the top of the cabin.

Donalson, who retired with the rank of major general, died in 1987. But during a recent stop in Birmingham, two of his grandchildren were among those who climbed aboard the resurrected aircraft. Granddaughter Denise Harris sat in one of the seats occupied by a paratrooper for the ride to France.

Harris struggled with the thought of being inside the same airplane her grandfather flew for the invasion in 1944.

“It’s unbelievable to think that all those men were in that plane also, and to hear the stories, and to know some of the people that came back,” she said.