It was a bustling Thursday morning at Mokuola.

Slightly overcast, the rain was holding off as visitors fished, played and strolled around what is also known locally as Coconut Island.

Lehua Kaulukukui of Waikoloa and Lilinoe Keliipio-Young of Keaukaha sat at a picnic table with photo albums before them, not far from where the Keliipio family used to reside.

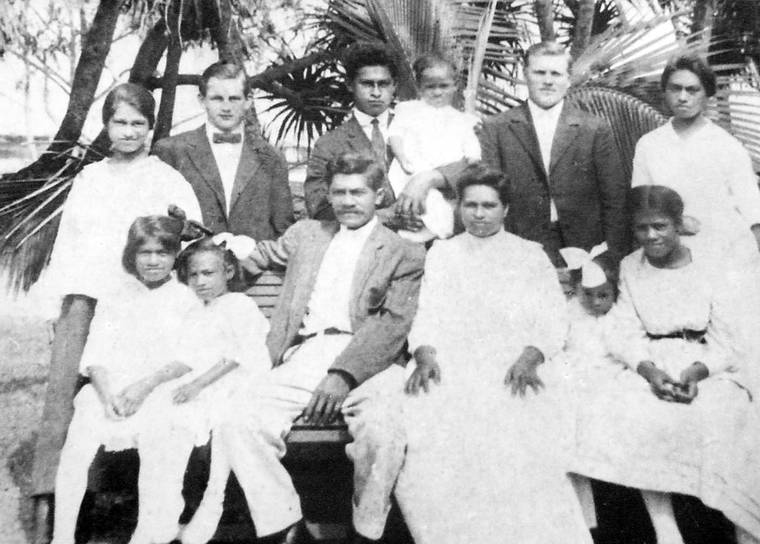

Keliipio-Young’s grandfather and Kaulukukui’s great-grandfather, Isaac Keliipio, served as the island’s caretaker from 1909 until he died in 1930.

His wife, Mary, then took over those duties until she retired in 1947, when their son, Paul Keliipio, Keliipio-Young’s father, became the island’s last resident caretaker.

Keliipio-Young said that according to county records, her grandfather was first employed as the steward of the area in 1909, but the family’s association with the island began earlier, around the turn of the century.

“He and my grandmother had five children, (and) came to live here and started to care-take this place. Eventually, in the almost quarter century of living here, their family grew from five to 14 (children) … and all of them were actively involved in taking care of this place, in finding innovative ways to use the resources around here to sustain a family of that size.”

When Isaac Keliipio died in 1930, Keliipio-Young said there were already grandchildren in the family.

“So they all lived around here, and so it took my grandmother and the children to continue the stewardship of the place until my father took over in 1947.”

Paul Keliipio remained the island’s caretaker until the 1960 tsunami “just wiped out this whole area and displaced all of us,” she said.

During her grandparents’ time on the island, Keliipio-Young said Mokuola was a gathering place for the community.

“So people would come here, and they would have band concerts and beauty contests and fishing derbies, and this was the spot to be at if you wanted any kind of recreational activities.”

Kaulukukui’s grandmother, Ku‘ualoha Keliipio, was the first paid lifeguard in the area, and other siblings followed suit in the intervening years.

Before a bridge to the island was built, visitors could only get there by rowboat — operated by family members — or swimming.

“When I was born in 1951, there was still no bridge, so my parents used the row boat to take us back and forth,” Keliipio-Young said.

Prior to the bridge being built later in 1951, the rowboat was used to supplement the family’s income, she said.

“And with 14 mouths to feed, the ocean became our refrigerator,” Keliipio-Young said. “My uncles and my aunts became very skilled at fishing, diving and gathering from the ocean — not only to sustain the family but to use excess that they collected to barter and trade for things that they couldn’t get here. So the rowboat became another source of supplementing the family’s income.”

It cost a nickel to cross — a lot of money in those days, she said.

Keliipio-Young spent the first nine years of her life on Mokuola and recounted tales from her childhood.

She and her friend would wave to incoming cruise ships, then take visiting tourists on walking tours, “and they would just buy us anything. We were like 8-, 9-year-old entrepreneurs. … We got to get free lunch and all the crack seed we wanted and all the treats we wanted.”

Water lapping against a wall near their house was her nightly lullaby.

“When we left here, the night we evacuated, we went to my aunt’s house that was like six blocks away from the ocean, and for about six months after that, my father had to take us by car every night to a beach so we could hear the ocean and fall asleep,” said Keliipio-Young.

Today, Mokuola is a place that anchors the family, she said.

“Sense of place is a very, very important thing in our culture,” she said. “If you know where you’re from and you know the history about that place, it’s easy to connect oneself to other people who have lived there. And there might not have been other families living on this island, but throughout this community up here, today you see (a) golf course, but when I lived here, there were 500, 600 homes.”

“And for me, one generation below Lilinoe, I just am amazed and enthralled every time Lilinoe speaks about this area and this island, and I love hearing the stories of the past about how she grew up here, and I put those pictures in my mind of what it must have been like to have grown up on this island … ,” Kaulukukui said. “And for our family, those are like little jewels, treasures for our family.”

A proclamation signed by Mayor Harry Kim has designated the first Saturday in May “Keliipio Ohana Day” on Mokuola.

Kaulukukui said the idea for the proclamation came after she had dinner with a cousin, who wanted to plan the next family reunion in Hilo, “and especially on Mokuola Island, just because of the family’s roots to this island.”

“And he told me that he would actually love to see a day just set aside for the Keliipio ohana to come and gather on the island … he said perhaps once a year,” she said. “When he was telling me this … I thought to myself, I really want to make this happen for him, and not just for him but for the whole family.”

While reunions have been held there in the past, and the family does gather here, Kaulukukui said there’s never been a dedicated day for the ohana.

“I see it as valuable for our younger generations to come and gather with us and sit with those that still have stories and experiences to share,” Keliipio-Young said.

The family recently lost a cousin in his 90s, “and they were here in the very early days when our grandparents lived here, and they helped with most of the duties that it took to take care of this place.”

“So those stories are passed down whenever we get together for family reunions. They’re shared,” she continued. “In order for those experiences to stay alive, it has to constantly be shared so our younger generation will realize the importance and the connections to this place here.”

The family will have a mini-gathering on the island the first Saturday in May. Keliipio-Young, who regularly gives lectures on the history of the island, will do a historical talk around 1 p.m. that day.

Email Stephanie Salmons at ssalmons@hawaiitribune-herald.com.