Hilo is all abuzz about one of its own, Jennifer A. Doudna, sharing the Nobel Prize in chemistry with co-researcher Emanuelle Charpentier of France.

While that was news to many, one retired biology professor at the University of Hawaii at Hilo has predicted for almost three decades that Doudna would become a Nobel laureate.

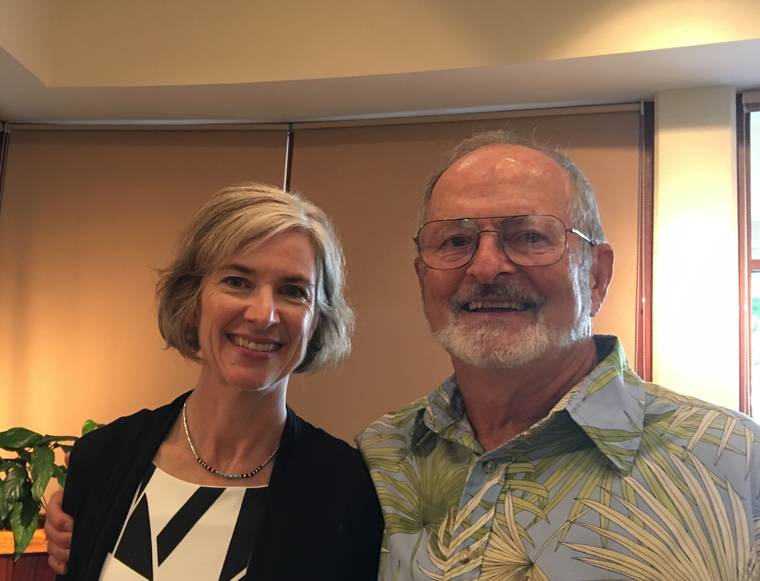

“You know, I told Martin, her dad, before he passed on, ‘I think your daughter is going to win the Nobel Prize. And that was before she did all the CRISPR stuff,” Don Hemmes told the Tribune-Herald on Wednesday, referring to Martin Doudna, a UH-Hilo English professor who died in December 1995.

CRISPR-Cas9, developed by Doudna and Charpentier, is a gene-editing tool that has revolutionized science by providing a way to alter DNA. The technology already is being used to try to cure a host of diseases and raise better crops and livestock.

“There is enormous power in this genetic tool,” said Claes Gustafsson, chairman of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, on Wednesday when the award winners were announced.

More than 100 clinical trials are underway to study using CRISPR — an acronym for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats — to treat inherited diseases, and “many are very promising,” according to Victor Dzau, president of the National Academy of Medicine.

“It opens a whole new field of gene editing,” added Hemmes. “You can edit them, correct them, hopefully. If it’s a mutation that’s causing a disease like sickle cell anemia, you can go in there and correct that gene very precisely. … If you read her book, ‘A Crack in Creation,’ of all the uses, already, for this CRISPR technology, you’d just be amazed — a lot in agriculture.”

Doudna, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, is a 1981 graduate of Hilo High School. She received her bachelor’s degree in biochemistry from Pomona College and her doctorate degree from Harvard Medical School.

Like her father, her late mother, Dorothy, also was an academic. She taught history at Hawaii Community College.

Hemmes saw the potential in Jennifer Doudna early.

“She came and worked in my lab at the university when she was still in high school, and she was bright and just so interested in everything she saw,” he said. “In those days, I was running the electron microscope, and with an electron microscope, you can look on the inside of cells and see things that are very tiny. And I think that got her interested in smaller and smaller things, like DNA and RNA.”

Hemmes told not only Doudna’s parents, but also his students as far back as the early 1990s that she would one day win a Nobel Prize.

Doudna told the Tribune-Herald in 2015 that she was inspired by a program sponsored by Hilo High during her junior year that brought scientists from throughout the state to speak to students. A woman from the University of Hawaii presented her work, detailing processes that took place at the molecular level.

“I was so fascinated by her work,” Doudna said.

Three times a woman has won a Nobel in the sciences by herself, but Wednesday was the first time an all-woman team won the science prize. In 1911, Marie Curie was the sole recipient of the chemistry award, as was Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin in 1964. In 1983, Barbara McClintock won the Nobel in medicine.

Charpentier, the 51-year-old leader of the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens in Berlin, said that while she considers herself first and foremost a scientist, “it’s reflective of the fact that science becomes more modern and involves more female leaders.”

The breakthrough research done by Charpentier and Doudna was published in 2012, making the discovery very recent compared with a lot of other Nobel-winning research, which is often honored only after decades have passed.

Dr. Francis Collins, who led the drive to map the human genome, said the technology “has changed everything” about how to approach diseases with a genetic cause.

“You can draw a direct line from the success of the human genome project to the power of CRISPR-Cas9 to make changes in the instruction book,” said Collins, director of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, which helped fund Doudna’s work.

The Broad Institute, jointly operated by Harvard and MIT, has been in a court fight with the Nobel winners over patents on CRISPR technology, and many other scientists did important work on it, but Doudna and Charpentier have been most consistently honored with prizes for turning it into an easily usable tool.

Scientists fear CRISPR will be misused to make “designer babies” by altering eggs, embryos or sperm — changes that can be passed on to future generations.

Much of the world became aware of CRISPR in 2018, when Chinese scientist He Jiankui revealed he helped make the world’s first gene-edited babies, to try to engineer resistance to infection from the AIDS virus. His work was denounced as unsafe human experimentation, and he has been sentenced to prison in China.

In September, an international panel of experts issued a report saying it is too soon to try such experiments because the science isn’t advanced enough to ensure safety.

“Being able to selectively edit genes means that you are playing God in a way,” said American Chemistry Society President Luis Echegoyen, a chemistry professor at the University of Texas El Paso.

Hemmes said Doudna has “been the person going out and talking about not using this on human embryos.”

Doudna told the Tribune-Herald in 2015 that she’s “been very involved in conversations” on bioethics regarding the use of the CRISPR technology.

“We need to understand better how (CRISPR) functions and how we can think about applying it,” she said.

The Associated Press contributed to this story.

Email John Burnett at jburnett@hawaiitribune-herald.com.