Volcanic gases are an important part of eruptions — they help magma to rise within the earth and erupt, they can tell us how much lava is being erupted, and the volcanic air pollution (vog) they cause can be a hazard. So it is important for the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory to measure how much of what kind of gas is being emitted by our volcanoes.

When people think about gas measurements, gas concentration — or how much gas there is in one spot at one time — is often what comes to mind. Knowing concentrations of gases like sulfur dioxide (SO2), for example, is important for understanding implications for human health during volcanic eruption.

Another number that volcanologists report is the emission rate of SO2 — how much SO2 is released over time by a volcano. But perhaps counterintuitively to those who are not volcanic gas specialists, the emission rate is not actually determined by directly measuring concentrations of SO2.

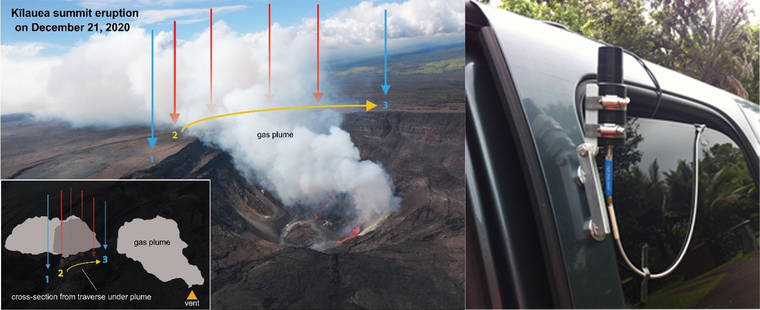

To measure SO2 emission rates, we begin by mounting an ultraviolet spectrometer to a car, aircraft, or backpack frame. Since SO2 is invisible and may not perfectly coincide with visible parts of the plume, we assess where the SO2 should be based on wind direction. Then, starting under clear sky on one side of the plume, we traverse underneath the entire width of the plume, and end up back under clear sky on the other side.

The spectrometer looks up at the sky and, because SO2 absorbs UV radiation, it detects less incoming UV when it is under the gas plume where there is SO2. It measures how much SO2 is above it in the vertical ‘path’ where the spectrometer is looking — the ‘concentration-path-length’.

Concentration-path-length combines concentration and path into a single unit, ppm∙m (parts per million meters). A 1-meter (about one yard) thick plume with a concentration of 10 ppm (parts per million) of SO2 is equivalent to 10 ppm∙m. So is a 10-meter (about 11 yards) thick plume with a concentration of only 1 ppm of SO2. The amount of SO2 is the same, it’s just distributed differently.

All those concentration-path-length measurements put together across the plume’s width make a ‘slice’, or cross-section, through the plume, showing how much SO2 was above the spectrometer at each point. That slice, since it incorporates the plume width in meters, is the area of the gas in a cross-section of plume, with units of ppm∙m2 (parts per million square meters).

Once we have that cross-section, we use plume speed (in meters/second) to determine how many of those cross-sections — and how much gas — are passing overhead in a certain amount of time. That brings us to units of ppm∙m3/s (parts per million cubic meters per second) — which is a volume of gas with a certain concentration of SO2 each second.

Because we know how much a molecule of SO2 weighs, we can convert that volume into a mass (in kilograms or metric tonnes), and we can convert seconds to days. That’s how we derive our emission rates of SO2, which are usually presented in units of tonnes/day (t/d).

So how do SO2 emission rates from the current eruption compare to previous eruptions at Kilauea?

When HVO began to routinely use these UV measurements in 1979, the summit averaged about 500 t/d of SO2 or less. Between 1983 and 2008, Kilauea’s Pu‘u ‘O‘o eruption averaged around 2,000 t/d. After higher emission rates early in the 2008–2018 summit eruption, the lava lake emissions stabilized near 5,000 t/d while Pu‘u ‘O‘o’s emissions fell to a few hundred t/d.

The 2018 eruption had incredibly high emission rates of nearly 200,000 t/d, the highest recorded emissions from Kilauea. Following the 2018 activity, total Kilauea emissions dropped to only about 30 t/d.

At the onset of the new eruption in December 2020, Kilauea summit emission rates were 30,000–40,000 t/d. Since the north fissure activity ceased on December 26, 2020, SO2 emissions have progressively dropped to around 2,500 t/d on January 11, 2021, telling us that the eruption rate has decreased.

Even with decreased levels of SO2 being emitted, measurements are still important because of hazards associated with vog, and because of what we can learn about eruption dynamics. So whatever happens next, HVO will continue using our ‘gas math’ to keep an eye on Kilauea’s SO2 emissions.

Volcano

activity updates

Kilauea Volcano is erupting. Its USGS Volcano Alert level is at WATCH (https://www.usgs.gov/natural-hazards/volcano-hazards/about-alert-levels). Kilauea updates are issued daily.

Lava activity is confined to Halema‘uma‘u with lava erupting from a vent on the northwest side of the crater. This morning, Jan. 14, the lava lake was about 199 m (653 ft) deep and remains stagnant over its eastern half. Sulfur dioxide emission rate measurements made on Monday (Jan. 11) were about 2,500 t/d, below the range of emission rates from the pre-2018 lava lake. Yesterday afternoon, summit tiltmeters began recording inflationary tilt. Seismicity remains elevated but stable, with steady elevated tremor and a few minor earthquakes. For the most current information on the eruption, see https://www.usgs.gov/volcanoes/Kilauea/current-eruption.

Mauna Loa is not erupting and remains at Volcano Alert Level ADVISORY. This alert level does not mean that an eruption is imminent or that progression to eruption from current level of unrest is certain. Mauna Loa updates are issued weekly.

This past week, about 50 small-magnitude earthquakes were recorded beneath the upper-elevations of Mauna Loa; most of these occurred at depths of less than 8 kilometers (about 5 miles).

The largest recorded earthquake was a M3.2 beneath the volcano’s upper Southwest Rift Zone on Jan. 8 at 4:23 p.m. HST. The earthquake activity on Mauna Loa’s northwest flank, which began on Dec. 4, 2020, has subsided to average long-term trends. Global Positioning System measurements recorded contraction across the summit caldera since mid-October with extension (summit inflation) resuming in the past few weeks, consistent with magma supply to the volcano’s shallow storage system. Gas concentrations and fumarole temperatures at both the summit and Sulphur Cone on the Southwest Rift Zone remain stable. Webcam views have revealed no changes to the landscape over the past week.

For more information on current monitoring of Mauna Loa Volcano, see: https://www.usgs.gov/volcanoes/mauna-loa/monitoring.

There were 2 events with 3 or more felt reports in the Hawaiian Islands during the past week: a M2.8 earthquake 19 km (11 mi) NW of Hawi at 28 km (17 mi) depth occurred on Jan. 10 at 7:32 p.m. HST and a M3.1 earthquake 20 km (12 mi) WNW of Volcano at 5 km (3 mi) depth occurred on Jan. 09 at 5:15 p.m. HST.

HVO continues to closely monitor both Kilauea’s ongoing eruption and Mauna Loa for any signs of increased activity.

Please visit HVO’s website for past Volcano Watch articles, Kilauea and Mauna Loa updates, volcano photos, maps, recent earthquake info, and more. Email questions to askHVO@usgs.gov.

Volcano Watch is a weekly article and activity update written by U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists and affiliates.