U.S. Rep. Ed Case said he’s “concerned” and “disgusted” that with less than two weeks remaining in the fiscal year, Congress hasn’t passed the necessary appropriations bills to avert a government shutdown that could come Oct. 1.

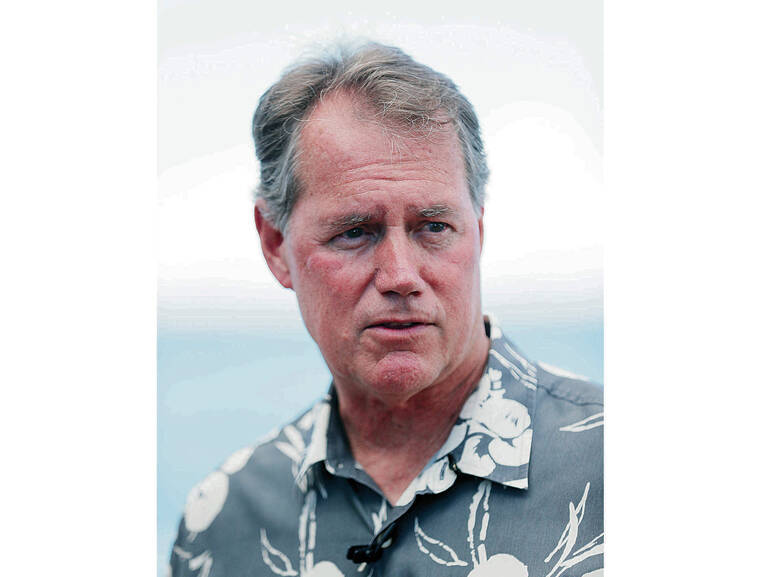

Case, a Democrat who represents urban Honolulu and is a member of the House Appropriations Committee, made that statement Monday during an online interview.

”The year I got back (to Washington), 2018-2019, was a full-blown government shutdown. The government did shut down,” Case said. “The next couple of years, we came right up to the brink and had to go with what we call a continuing resolution, which is kind of a fancy way to say we’re going to continue to spend the same amounts for the same programs as last year while we figure out how to get done what we should’ve gotten done by the end of the fiscal year.

And these CRs, as we call them, are highly problematic for our federal agencies in terms of predictability, in terms of funding — especially for the Department of Defense, where it just messes up their procurement programs. Certainly, I want to get the appropriations bills for the coming fiscal year. … So by October 1 … we should have passed all our appropriations bills and authorized spending for the next year for our federal government, some $1.6 trillion worth of federal spending. We have not done that today, and so we are negotiating a continuing resolution right now, that we need to pass to avoid any kind of government shutdown.”

Case, who is in Washington, D.C., said members of Congress are in the U.S. capital trying to avert a shutdown.

“I don’t think we will actually have a government shutdown,” he said. “I think the atmosphere that we’re working in is trending toward some sort of continuing resolution to buy us some time to get the appropriations bills done, but it is a concern. And, again, it does not reflect well on our government in a very continuing partisan and divided time.”

Case said he also is concerned about inflation — especially in Hawaii.

With the annual U.S. inflation rate at 8.3% for the 12 months ending in Aug. 22, Case said the Jones Act — which requires that cargo shipped between U.S. ports must be on U.S.-flagged, American-made vessels with American ownership and crews — has hurt Hawaii residents’ pocketbooks even more.

“We don’t have the options of a train down here from California or a truck. We rely on our shipping,” he said. “And if shipping is captured by just a few companies, as it is, then prices go up. And it is. We’re probably paying somewhere around 20, 25% extra than the mainland, across the board.”

According to Case, studies show the Jones Act, which is formally the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, costs every person in Hawaii about $650 a year.

“Now, the Jones Act has a particular impact in the post-Ukraine-Russian embargo situation, because we were getting upwards of 25% of our fossil fuel in Hawaii directly from overseas,” he said. “The reason we did that is because the Jones Act made it too expensive to bring it in from the continent.

“ … So, I asked the president some months ago to waive the Jones Act in the case of getting oil into Hawaii from the continent during the Ukraine emergency. And in so many words, what the administration responded was, ‘Well, if it gets to be that kind of a problem where you are actually not finding oil on the world market to replace Russia in Hawaii, then we’ll consider that waiver.’

“We haven’t been in that situation yet, because we have been able to buy oil in other places on the world market.”

Email John Burnett at jburnett@hawaiitribune-herald.com.