Walter Dudley was finishing up a lecture at the University of Hawaii at Hilo in the early 1980s when inspiration struck.

He was teaching marine science to a night class of veterans and, having served as an Army engineer officer and a counterintelligence agent, he would talk story with students during the break.

“I was giving a scientific lecture on tsunamis, and during the break, they started telling me their own stories,” Dudley said. “They were really mind-blowing, and I asked if anybody had written these down, and they said, no, nobody’s ever been interested, and I thought these are very powerful and important, so I started collecting stories.”

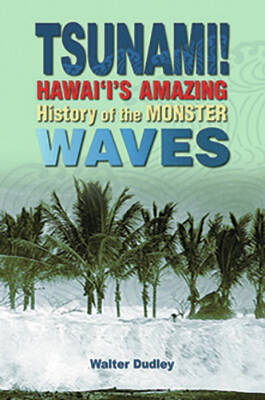

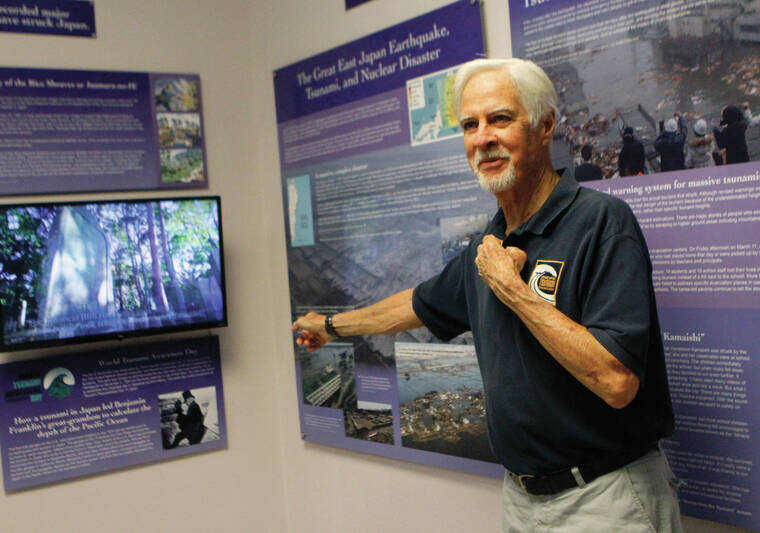

The experience led to a lifelong passion for Dudley, who has interviewed over 500 tsunami survivors across the globe, opened the Pacific Tsunami Museum in Hilo, and published several books on the subject, including the newly released “Tsunami! Hawaii’s Amazing History of the Monster Waves” from Mutual Publishing.

His collection of survivor stories not only help educate people about the dangers of tsunamis, but also highlight the ways people can prepare for the monster waves and predict when they will crash again.

“If history were taught as stories, it would never be forgotten — famous quote, but it’s very true,” Dudley said. “I ultimately wrote my first book on tsunamis to try and explain both how they work and what the real danger is.”

That first book was titled “Tsunami!” and featured images and stories from the 1946 tsunami that hit Hawaii Island.

The waves were triggered by a 7.4-magnitude earthquake off the coast of Alaska that led to the death of 158 people. Surges were the size of three-story buildings, with a maximum height of 45 feet recorded.

Shortly after publication, a Hawaii Island survivor reached out to Dudley to share her own story.

“She had grown up as a little girl in Keaukaha, and as a 6-year-old, she had ran away from the tsunami with her little brother who was 4, back into the jungle while their house was being picked up and washed away,” Dudley said. “When she took me out there on the site and told me her story, she said, ‘You know, we should really start a museum to collect these stories,’ and I agreed with her.”

That survivor was Jeanne Branch Johnston, and together, she and Dudley co-founded the Pacific Tsunami Museum, which opened in 1993.

“We managed to get some federal grant money, and we were very lucky in that the bank building was given to us, where the museum is located today,” Dudley said. “People will still come into the museum and tell us a story, and not a year goes by we don’t have someone who has a tsunami story we never heard about.”

The museum continues to update its exhibitions. A showcase on the South Pacific tsunami of 2009 will open soon with stories from Dudley’s interviews with over 50 survivors.

“There’s so many close parallels between Hawaii and Samoa,” Dudley said of the exhibit. “We also want to tell more of the Native Hawaiian history with tsunamis, because they’ve been impacted going back as long as there have been any humans on the islands.”

One of the last deadly tsunamis to touch down on Hawaii Island occurred in 1960, and stories from the experience can be found throughout the museum.

“It’s been so many years, that a lot of the survivors are no longer with us. They’ve passed away. And one of the missions of the museum is to keep their stories alive,” Dudley said. “From each one of these events we learn things, we learn mistakes were made, and we learn things that will help us become better prepared.”

Those lessons, Dudley explains, center around improving training for first responders, incorporating regular drills into schools, practicing evacuations, and informing travelers of early warning signs. These can include earthquakes, a loud roar from the ocean, and other unusual ocean behavior like a fast-rising floor or a sudden loss of water resembling very low tide.

“If it’s a local tsunami on the Big Island, we may have five minutes, 15 minutes, depending on where it comes from,” Dudley said. “The odds of another tsunami increase every year, too, because there are all these areas around the Pacific rim called seismic gaps that normally have earthquakes periodically, and they haven’t had one in a long time.

“It’s not if,” he added. “But when.”

His new book features a new collection of photographs and stories. These include a Hilo Boy Scout Troop that experienced the 1975 tsunami at Halape, a waitress working at the Naniloa Hotel who was saved by a Japanese POW and his Army guard, and the unexpected reunion of a survivor with the man who rescued him that all began when the survivor was recognized by his children in a photo during a visit to the museum.

“It’s really difficult for people to lose friends, but for people to lose family — especially parents who lose their children — they never get over that,” Dudley said. “A lot of people said it was very difficult opening up at first, but when we explained that by sharing their story we were going to help save other people’s lives, almost everyone said it was cathartic.

“Afterwards, they felt so much better and thanked us, because it really took a lot of weight off of them.”

Dudley’s new book, “Tsunami! Hawaii’s Amazing History of the Monster Waves,” is available this month and can be purchased at https://tinyurl.com/mxcfmmh8 and at local bookstores.

Email Grant Phillips at gphillips@hawaiitribune-herald.com.