A tantalizing ‘hint’ that astronomers got dark energy all wrong

On Thursday, astronomers who are conducting what they describe as the biggest and most precise survey yet of the history of the universe announced that they might have discovered a major flaw in their understanding of dark energy, the mysterious force that is speeding up the expansion of the cosmos.

Dark energy was assumed to be a constant force in the universe, both currently and throughout cosmic history. But the new data suggest that it may be more changeable, growing stronger or weaker over time, reversing or even fading away.

ADVERTISING

“As Biden would say, it’s a BFD,” said Adam Riess, an astronomer at Johns Hopkins University and the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. He shared the 2011 Nobel Prize in physics with two other astronomers for the discovery of dark energy, but was not involved in this new study. “It may be the first real clue we have gotten about the nature of dark energy in 25 years,” he said.

That conclusion, if confirmed, could liberate astronomers — and the rest of us — from a long-standing, grim prediction about the ultimate fate of the universe. If the work of dark energy were constant over time, it would eventually push all the stars and galaxies so far apart that even atoms would be torn asunder, sapping the universe of all life, light, energy and thought, and condemning it to an everlasting case of the cosmic blahs. Instead, it seems, dark energy is capable of changing course and pointing the cosmos toward a richer future.

The key words are “might” and “could.” The new finding has about a 1-in-400 chance of being a statistical fluke, a degree of uncertainty called three sigma, which is far short of the gold standard for a discovery, called five sigma: 1 chance in 1.7 million. In the history of physics, even five-sigma events have evaporated when more data or better interpretations of the data emerged.

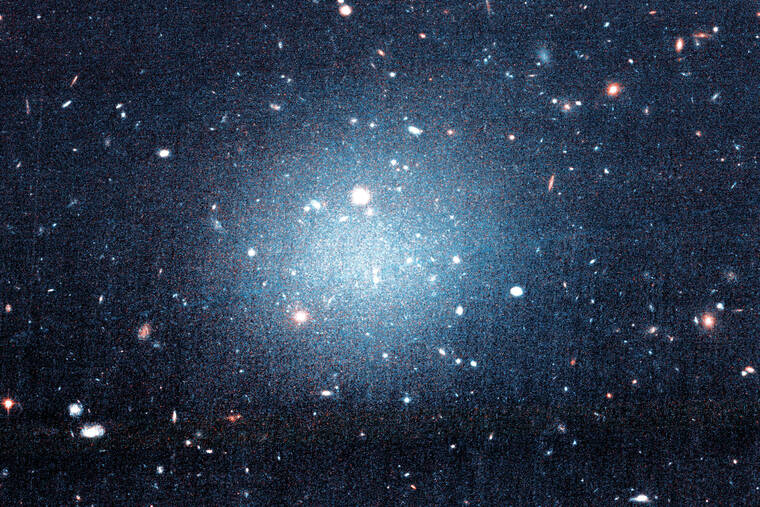

This news comes in the first progress report, published as a series of papers, by a large international collaboration called the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument, or DESI. The group has just begun a five-year effort to create a 3D map of the positions and velocities of 40 million galaxies across 11 billion years of cosmic time. Its initial map, based on the first year of observations, includes just 6 million galaxies. The results were released Thursday at a meeting of the American Physical Society in Sacramento, California, and at the Rencontres de Moriond conference in Italy.

“So far we’re seeing basic agreement with our best model of the universe, but we’re also seeing some potentially interesting differences that could indicate that dark energy is evolving with time,” Michael Levi, the director of DESI, said in a statement issued by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which manages the project.

The DESI team had not expected to hit pay dirt so soon, Nathalie Palanque-Delabrouille, an astrophysicist at the Lawrence Berkeley lab and a spokesperson for the project, said in an interview. The first year of results were designed to simply confirm what was already known, she said: “We thought that we would basically validate the standard model.”

But the unknown leaped out at them.

When the scientists combined their map with other cosmological data, they were surprised to find that it did not quite agree with the otherwise reliable standard model of the universe, which assumes that dark energy is constant and unchanging. A varying dark energy fit the data points better.

Wendy Freedman, an astrophysicist at the University of Chicago who has led efforts to measure the expansion of the universe, praised the new survey as “superb data.” The results, she said, “open the potential for a new window into understanding dark energy, the dominant component of the universe, which remains the biggest mystery in cosmology. Pretty exciting.”

Michael Turner, an emeritus professor at the University of Chicago who coined the term “dark energy,” said in an email: “While combining data sets is tricky, and these are early results from DESI, the possible evidence that dark energy is not constant is the best news I have heard since cosmic acceleration was firmly established 20-plus years ago.”

The DESI project, 14 years in the making, was designed to test the constancy of dark energy by measuring how fast the universe was expanding at various times in the past. To do that, scientists outfitted a telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory with 5,000 fiber-optic detectors that could conduct spectroscopy on that many galaxies simultaneously and find out how fast they were moving away from Earth.

© 2024 The New York Times Company