Island of Hawaii residents are used to feeling the ground shake beneath them. From subtle shakes that feel like wind, to abrupt jolting that knocks dishes off the counter, living on this volcanically active island means accepting that the ground beneath our feet will not always keep still.

The most recent notable felt earthquake happened on Saturday night, July 6, at 8:47 p.m HST. The magnitude (M) 4.1 earthquake was on Kilauea’s south flank at a depth of about 7 km (4.4 miles) below sea level. This event produced a handful of aftershocks, including three above M2 that occurred within ten minutes of the M4.1.

Earthquakes that occur on Kilauea’s south flank typically happen on either the Hilina fault system or the fault called the “décollement.” The steep faults of the Hilina fault system are easy to visualize as they appear on the surface as steep pali (cliffs) along the southeast coast of the Island of Hawaii. These steep faults continue through the subsurface and can produce large earthquakes as rocks along the nearly vertical faults slip against each other.

The décollement, or detachment fault, sits beneath the Hilina fault system. This fault is nearly horizontal beneath Kilauea’s south flank at the interface between the island and the ocean floor. This interface can produce larger events and, according to seismologists at the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO), was the likely source of Saturday’s M4.1 based on the depth and motion.

Slip along the décollement can be produced as a combination of gravity and changes in pressure occurring in the volcano that sits above. In the past 50 years, there have been three décollement earthquakes above M6 on Kilauea’s south flank.

The most recent was the M6.9 earthquake that occurred on May 4, 2018. This earthquake was caused by the magmatic intrusion in Kilauea’s East Rift Zone, which led to the 2018 eruption in the lower East Rift Zone.

The décollement also produced a M6.2 earthquake in 1989. This event caused injuries, destroyed or damaged houses in Puna District, caused landslides that blocked roads, and generated a small local tsunami.

The most destructive of the three events was in 1975, and it was the largest earthquake in Hawaii since 1868. A M7.7 on the décollement fault beneath Kilauea caused several meters (yards) of horizontal and vertical movement along faults in the summit and south flank regions. The earthquakes caused building and road damage, along with a tsunami that resulted in two local fatalities.

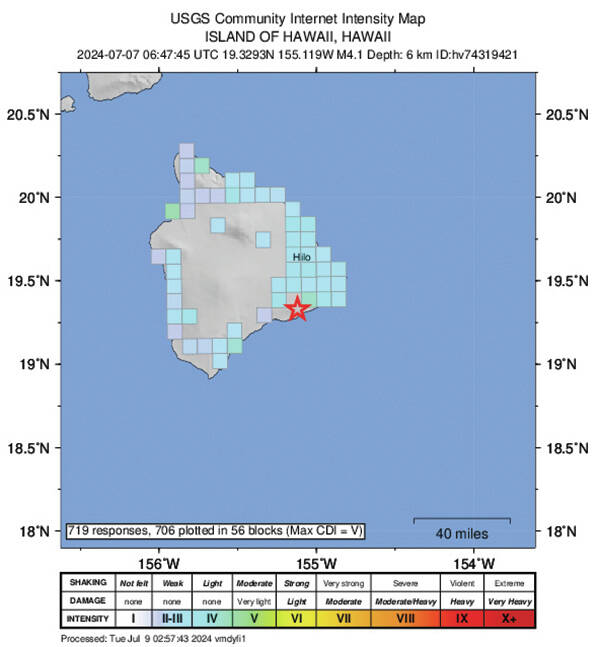

Within this greater context, Saturday’s M4.1 was only a minor slip along Kilauea’s décollement, but its widely felt shaking serves as a reminder of the potential for this region to produce damaging and widely felt earthquakes. More than 700 people reported feeling the recent M4.1, spanning the Island of Hawaii and even as far as Maui and Lanai.

As residents of a very shaky island chain, the USGS “Did you feel it?” website is a phenomenal resource that citizens and scientists alike can use to report how we individually feel earthquakes.

While the magnitude of an earthquake is the size derived from data collected by the network of seismic instruments, the intensity of an earthquake is a measure of shaking derived from the network of people reporting how they felt it. Based on the felt reports, “Community Internet Intensity Maps” or CIIMS are generated in near real-time and help us understand how different types of earthquakes can impact different regions in Hawaii.

The USGS Fact Sheet “Did You Feel It? Citizens contribute to Earthquake Science” describes the importance of CIIMs: “…as a result of work by the U.S. Geological Survey and with the cooperation of various regional seismic networks, people who experience an earthquake can go online and share information about its effects to help create a map of shaking intensities and damage…CIIMs contribute greatly toward the quick assessment of the scope of an earthquake emergency and provide valuable data for earthquake research.”

The next time you feel an earthquake, first ensure that you and your surroundings are safe. Then, if you would like to support the science happening in Hawaii, please fill out your felt report. Mahalo to everyone who reports feeling earthquakes in Hawaii; your reports help us understand impacts of earthquakes in our dynamic environment.

Volcano activity updates

Kilauea is not erupting. Its USGS Volcano Alert level is ADVISORY.

Elevated earthquake activity and inflationary ground deformation rates continue in Kilauea’s summit region, indicating that magma is repressurizing the storage system. Over the past week, about 550 events (most were smaller than M2) occurred beneath Kilauea’s summit region and extending southeast into the upper East Rift Zone. Unrest may continue to wax and wane with changes to the input of magma; changes can occur quickly, as can the potential for eruption. The most recent summit sulfur dioxide emission rate measured was approximately 60 tonnes per day on July 9, 2024.

Mauna Loa is not erupting. Its USGS Volcano Alert Level is at NORMAL.

Four earthquakes were reported felt in the Hawaiian Islands during the past week: a M3.4 earthquake 0 km (0 mi) W of Pahala at 32 km (20 mi) depth on July 8 at 12:39 p.m. HST, a M1.9 earthquake 7 km (4 mi) SW of Volcano at 1 km (1 mi) depth on July 7 at 6:56 a.m. HST, a M3.3 earthquake 14 km (8 mi) S of Fern Forest at 6 km (4 mi) depth on July 6 at 8:51 p.m. HST, a M4.1 earthquake 15 km (9 mi) S of Fern Forest at 6 km (4 mi) depth on July 6 at 8:47 p.m. HST.

HVO continues to closely monitor Kilauea and Mauna Loa.

Please visit HVO’s website for past Volcano Watch articles, Kilauea and Mauna Loa updates, volcano photos, maps, recent earthquake information, and more. Email questions to askHVO@usgs.gov.