Newsom tries to understand ‘bro culture.’ Will it change him in the process?

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — It was a surprising revelation at the start of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s new podcast. His son had become a fan of Charlie Kirk, the right-wing influencer who mobilized young voters for Donald Trump.

Newsom, the Democratic governor of California, said that 13-year-old Hunter was such an admirer that he argued his father should let him attend the taping with Kirk. “‘What time? What time is Charlie going to be here?’” Newsom recounted his son saying at bedtime. “And I’m like, ‘Dude, you’re in school tomorrow.’”

ADVERTISING

That Kirk had captivated the son of a leading Democrat and a feminist documentarian, Jennifer Siebel Newsom, was an indication of just how popular conservative podcasters had become with young men.

Many expected Newsom to respond to Trump’s presidential victory by seizing the mantle as the voice of the resistance. Instead, he has become a different kind of voice entirely — the one on the podcast.

The governor has been using his new platform to explore what Democrats need to do to win back young men. Along the way, he has tried to charm far-right figures, angering many in his own party and inspiring critiques that he’s attempting to remake his image as a member of the liberal elite with well-coifed hair as he eyes a potential run for president in 2028.

The first three guests on Newsom’s show — officially titled “This Is Gavin Newsom” — were conservative men who have enraged Democrats in the past. Besides Kirk, who has criticized same-sex marriage and diversity programs, there was also Steve Bannon, an architect of the MAGA movement, and Michael Savage, a conservative talk show firebrand.

Concepts of masculinity have been a recurring theme with both conservative and liberal guests, as Newsom has delved into the “bro culture” that helped Trump defeat former Vice President Kamala Harris.

“This issue of young men and what’s happened to our party is deeply on my mind and will be deeply part of my podcast,” Newsom said in an interview with The New York Times. What he’s trying to explore, he added, are “the things that we’re uncomfortable exploring.”

It’s a remarkable shift for a politician who campaigned for governor in 2018 with his toddler on his hip and who, the next year, announced new tax breaks on diapers and menstrual products surrounded by boxes of Huggies and Tampax.

Now, Newsom is in his final year and a half in office with California facing numerous problems. The Los Angeles region is rebuilding two communities after the most destructive wildfires in Southern California’s history. Homelessness remains pervasive. The state budget is teetering.

In the midst of this, Newsom has used a podcast to embark on a political vision quest. “This is a selfish endeavor for me to understand the world I’m living in,” he said.

For several minutes on a recent episode, Newsom and Gov. Tim Walz of Minnesota, last year’s Democratic nominee for vice president, debated whether the party could — or should — try to appeal to men who may not share their social values.

Walz was reluctant: “I can’t message to misogynists.” He was likewise dismissive of conservative commentators, including the ones Newsom had interviewed. “How do we push some of those guys back under a rock?” Walz said, calling them “bad guys.”

Newsom said that referring to men as “misogynists,” as Walz did, was a political misstep.

“There’s a crisis of men and masculinity in this country,” Newsom said. “And that’s a hard thing for Democrats because we want to lift up women. We want to lift up the oppressed.”

Seeking wisdom from a Roman

Lately, Newsom has found solace in Stoicism, an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy that is enjoying a renaissance among some athletes and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs as a masculine guide for self improvement. It teaches self discipline and emotional resilience, emphasizing that the key to success is mastering the things you can control while maintaining calm about the things you can’t.

Newsom was turned on to the concept last year when he received “Meditations” by Marcus Aurelius, the ancient Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher. He has read it repeatedly.

The teachings “hit me like a lightning bolt,” he said. “Where the hell has this book been all my life?”

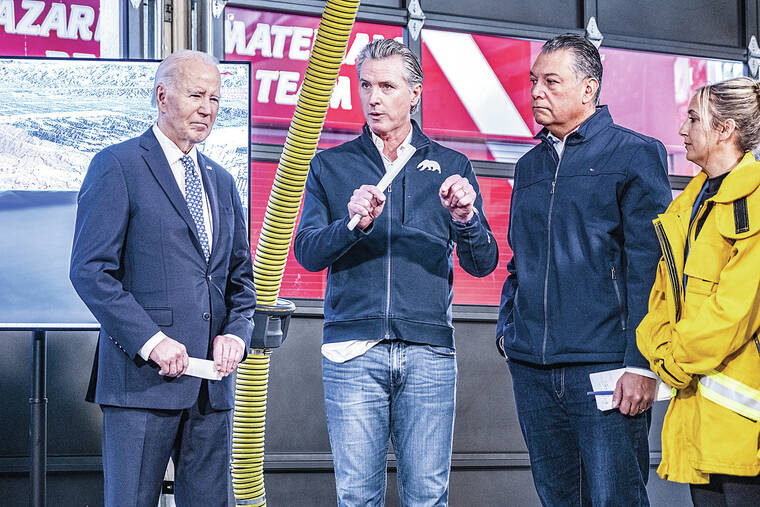

Since the November election, Newsom has visited conservative parts of California to tout economic development ideas. Last week, he stood before a row of fire trucks in the Central Valley town of Modesto, California, to present a career education plan for students who were not college-bound.

Republicans have mocked his shift. Greg Gutfeld, Fox News’ late-night satirist, scoffed at the idea that Newsom and Walz were trying to define masculinity for the Democratic Party. Gutfeld played one clip in which he compared Newsom’s hand gestures — something the governor often does in the throes of riffing on an idea — to milking a cow.

On the left, the governor’s decision to engage with Kirk has infuriated Newsom’s allies. Jodi Hicks, president of Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California, said that she welcomes Newsom’s effort to explore why Democrats lost votes of young men and try to find better ways to communicate. But Kirk’s positions against LGBTQ+ rights amount to “hateful rhetoric that is harmful to our young men,” she said.

“It’s toxic masculinity,” Hicks said. “I don’t think you have to invite those folks on and give them a platform to explore how we can do better for our young men.”

Why he split from Democrats on transgender athletes

It was Newsom’s podcast musings on transgender athletes that drew particular attention. He broke with fellow Democrats when he agreed with Kirk that it’s “deeply unfair” for transgender athletes to compete against participants who were born female.

To some, it seemed like another calculated move. But Newsom had long felt conflicted about the issue, said Jason Elliott, a former deputy chief of staff to the governor who was also one of his top aides when Newsom was mayor of San Francisco. Because sports played a big role in developing his self-confidence, Newsom wrestled with the idea that some girls could lose opportunities to transgender athletes with a physiological advantage, Elliott said.

“Often, things that he has told us privately eventually seep their way into public discussion,” he said.

Newsom has a record of expanding transgender rights. But the issue of athletic competition is different, he explained in the interview, because it “impedes other people’s rights.”

“Can’t we see that?” he said. “I don’t know what’s happened.”

Wade Crowfoot, a friend of Newsom who is also his secretary of natural resources, said Newsom has long been fascinated with conservative media and routinely talks about what’s on Fox News, sometimes bringing it up on their weekend hikes in Marin County or while fishing small lakes in the Sierra Nevada.

“He’s never been afraid to buck orthodoxy and by that, I mean advance something outside of the comfort zone of the Democratic Party,” Crowfoot said.

Early in Newsom’s career, that meant pushing the party to the left by allowing same-sex couples in San Francisco to marry in 2004. In recent years, the governor has pushed the party to the right at times, such as applauding conservative Supreme Court justices for ruling that local governments can clear homeless people from the streets.

Newsom’s podcast turn may have seemed out of nowhere, but it’s not the first time he has launched a talk show.

He hosted a local radio program when he was the mayor of San Francisco. As lieutenant governor, he hosted a television show on Current TV, a defunct cable network, in which he interviewed figures from Hollywood and Silicon Valley.

Then, as now, Newsom explained the rationale for his program by saying he wanted to make public some of the conversations he has in private.

One interview from 2012 stands out in hindsight. As with his new podcast, Newsom was deferential, in awe of the ideas explained by his guest. The guest, in turn, was eager and personable. Humble, even.

The entrepreneur talked about his failures, his low points, the time he had to borrow money from friends. And how he made a big bet on a space company that he thought would fail.

“If something’s important enough, it’s still worth doing, even if the odds of success are low,” Elon Musk said.

Newsom was enamored with the idea of Musk taking such big risks with Tesla, SpaceX and PayPal. He kept asking for more details, almost egging him on.

And, he observed, with a grin, “You’re just not a guy who’s going to sit on the beach and watch the waves come crashing in.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company