Big Island agriculture hit hard by vog

KAILUA-KONA — A week and a half after the earth split open in Puna and the hazards of Kilauea began devouring and toxifying everything in their path, 67-year-old Garuda Johnson looked out his window.

KAILUA-KONA — A week and a half after the earth split open in Puna and the hazards of Kilauea began devouring and toxifying everything in their path, 67-year-old Garuda Johnson looked out his window.

Seeing through the sulfur dioxide-laced haze of vog — which has measured quantities of SO2 as high as 10 parts per million (ppm) on Johnson’s personal monitor — is nearly impossible at distance.

ADVERTISING

But at close range, he could see well enough to make out just how extensively volcanic emissions had ravaged his 20-acre Pahoa farm on Kamaili Road, just a few miles from the doorstep of Kilauea’s destruction.

“The vegetables were dead, they died first,” said Johnson, owner and operator of Johnson Family Farms. “The vegetables just started turning white and they were just gone. All of them.”

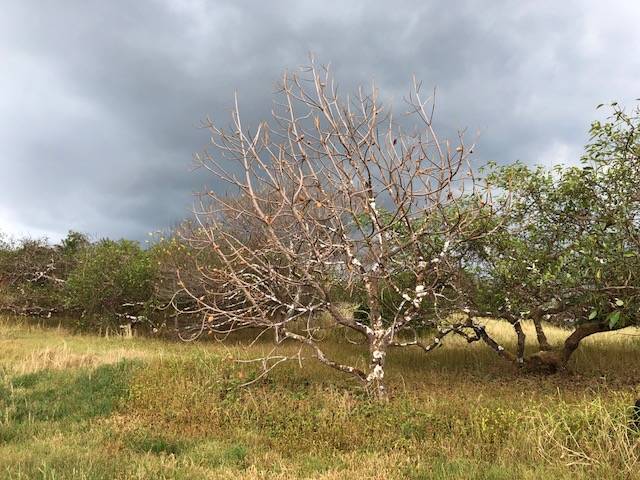

Tomatoes, lettuce, beets, radishes, more — all were wiped out. Next were most of Johnson’s 400 avocado trees, first their leaves and then their fruit. Tens of thousands of seedlings in the farm’s start room perished as well.

His business in ruins and any hope of a profit this year squandered, Johnson, his family and roughly a dozen employees had no choice but to abandon the property, which is home to seven people. The only hope to which Johnson continues to cling, albeit tenuously, is that lava won’t slide down from the volcano to claim what’s left.

“We lost where we lived,” Johnson said.

“This possibly killed the farm forever,” he continued. “I passed this on to my children, and they were (going) to pass it on their children. That’s something Hawaii really can’t afford to lose, even on a small scale like this.”

Death in the air

Responders have counted no human casualties since Kilauea stormed to life beneath the ground of Leilani Estates May 3. But the volcano is still claiming living things.

Sulfur dioxide — or SO2, a primary and harmful component of vog — infiltrates leaf mesophyll tissue by way of the stomata, openings in leaf surfaces that regulate the exchange of gasses, according to a 2008 report compiled by the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources.

Plants particularly sensitive to SO2 become symptomatic, showing lesions on both sides of the leaves between veins or along their edges ranging in color from tan to white to orange-red to brown, after eight hours of exposure to an air quality registering at less than 1 ppm of SO2.

“You see almost like burn marks on the leaves,” said Ken Love, executive director of Hawaii Tropical Fruit Growers.

Even the most resistant plants suffer consequences after 30 minutes of exposure to the 10 ppm levels Johnson has registered multiple times at his farm.

When SO2 combines with rain water, it becomes sulfuric acid. That acid rain increases soil acidity, decreases soil fertility and can lead to both reduced plant growth and fertility as well as foliage and flower damage, according to the CTAHR report.

And much the same as people, harmful elements of vog attack the youngest and weakest plant life most ferociously.

Ash fall accumulation also blocks out the sun and disrupts the photosynthesis process.

Love said farmers should only rinse ash off with water as a last resort. If ash gets wet but isn’t removed entirely from the leaf, it cakes and “becomes like cement.” He suggested using a blower or shaking trees to remove ash whenever possible.

Bearing fruit

Vegetables have proven most vulnerable to high concentrations of SO2. Fruits, while not immune, have shown greater resiliency.

Oscar Jaitt, who started in 1990 the Pahoa-based Fruit Lover’s Nursery just a few miles down the road from Johnson Family Farms, sold tropical fruit trees most of the last 28 years. He later transitioned to a mail-order seed business and sells tropical fruit seeds worldwide.

Specializing in rare and endangered species, Jaitt said about 5 percent of flora on his nearly 27 acres has been severely affected by poor air quality.

“Trees that naturally drop their leaves at a certain time of the year … those trees have all dropped their leaves, but not over a period of time like they naturally would do,” Jaitt said. “The leaves got brown and they dropped them all at once.”

Citrus trees appear particularly resilient to the predatory whims of vog, as do bananas. But while much of Jaitt’s produce is alive and yet able to be salvaged, many of his seedlings are suffering. And the conditions make his crop nearly impossible to tend during what is his most lucrative season.

Jaitt, who has remained on his property but can’t transport heavy machinery or employees in and out of the area, often struggles to breathe. At times, it’s even difficult to gather and sort thoughts.

“Imagine running a business and you can’t even think clearly,” Jaitt said.

He’s stopped taking orders on his website indefinitely. Just a couple miles from major cracks in the earth, were lava to begin flowing, Jaitt said he’d have a matter of minutes to clear out. The risk of losing everything has forced him to see a new perspective.

“I could lose my whole existence basically, and what I’ve been doing for the last 28 years,” Jaitt said. “If that happens, I would basically have to change my whole life. So the business seems like a very small aspect at this point.”

Cattle concerns

Livestock isn’t immune to vog, and CTAHR has advised ranchers to be on the lookout for eye irritation, weakness, abnormal behaviors or animals struggling to breathe.

The warning includes protecting a clean water supply and fluorine toxicity due to ash fall covering pasture land, which can be fatal to livestock. There is also a focus on mineral supplementation.

“Sulfur dioxide … may deplete livestock of selenium, copper, other minerals and vitamins essential for animal health,” a CTAHR release read.

Guy Galimba, a rancher with land both above and below Naalehu, said most of his roughly 2,500 head of cattle graze between 20-25 miles away from Kilauea. While it remains business as usual at his operation, his primary concern is the animals’ food source.

“In 2008, I had some pasture closer to Pahala and the regrowth was half of what it would normally be,” Galimba said. “So if that happens here, I would probably have to destock a little.”

He said it’s too early notice illnesses in the animals, which he believes won’t become apparent for several months, if they occur at all.

Economic Impact

Hawaii County Councilman Tim Richards said in an interview last week he suspected the island’s agriculture could suffer to the tune of tens of millions of dollars due to recent volcanic activity.

Johnson said that estimate sounded legitimate, adding that depending on how one calculates and extrapolates economic loss, impact could be significantly worse.

For instance, Johnson turns roughly $100,000 annually in avocados alone from trees that would likely have produced for decades.

“If trees don’t come back, you’re going to lose that income forever,” said Johnson, adding that it takes six to eight years to see a reasonable yield after planting new avocado trees — without accounting for a potentially higher soil toxicity leading to a lower and or slower yield.

“Just for me alone, that would be millions over a (long enough) period of time,” he continued. “And that’s just one guy.”

Jaitt said while he doesn’t have crop insurance, his homeowner’s insurance covers plant loss and he’s considering making a claim. However, coming up with accurate figures may prove tricky.

“How much is a ground tree worth? I don’t think really anybody can put a price on a rare tree that’s full grown. That’s very complicated.”

Love said the persistent vog has already produced economic effects as far away as West Hawaii, where SO2 levels are considerably lower than on the island’s Southeast side.

He’s noticed damage to achachairu and white sapote fruit trees only three weeks in.

Vog has hit different cacao relatives, known as theobroma, the worst so far.

“This (damage) could be from something else, but I haven’t noticed it before and all of the sudden it’s there,” Love said.

“Agriculturally, there’s a lot of problems down the line that we haven’t really seen. We’re just at the tip of the iceberg.”

Farmers and ranchers interested to know more can contact CTAHR, which is offering water and soil testing free of charge. Funds for the initiative, however, are limited.