Pahoa Elementary students return to school following summer of eruptions

HOLLYN JOHNSON/Tribune-Herald From left, fifth and sixth graders Kaulana Chow, 11, Brayden Conda-Tolle, 11, Madayson Freitas, 10, Isabella Tokelau, 10, and Aolani Lynch, 10, get to know each other by playing the board game “Sorry” with school counselor Evette Tampos Tuesday at Pahoa Elementary School.

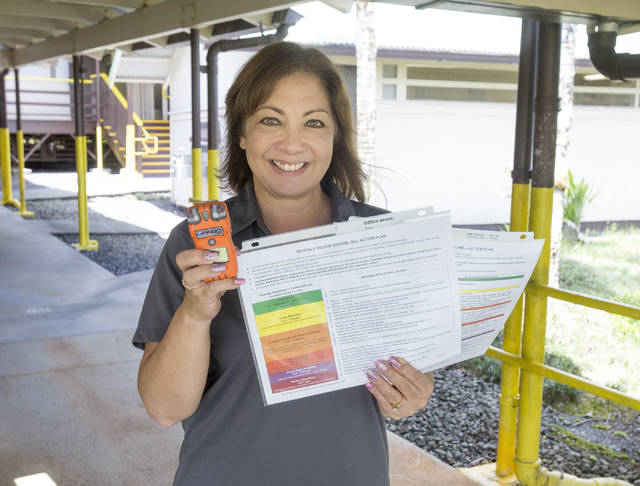

HOLLYN JOHNSON/Tribune-Herald Pahoa Elementary Principal Michelle Payne-Arakaki holds an SO2 monitor and the school’s sulfur dioxide action plan Tuesday at Pahoa Elementary School.

HOLLYN JOHNSON/Tribune-Herald Amber Makuakane hugs her son, AJ Maukakane, 4, Tuesday at Pahoa Elementary School.

It was quiet on the campus of Pahoa Elementary School on Tuesday morning.

It was quiet on the campus of Pahoa Elementary School on Tuesday morning.

By 10 a.m., the morning rush was long finished, and students were settled in their classrooms.

ADVERTISING

Pahoa Elementary Principal Michelle Payne-Arakaki said the students “all seemed happy. It was nice to see them happy.”

It was the first day back for the students after a summer interrupted by ongoing eruption activity in lower Puna, which began in May as the last school year was drawing to a close.

It’s so far, so good, Payne-Arakaki said, but it will take some time to get a better feel for how much impact the Kilauea eruption has had.

But the school is prepared, with two counselors and two school-based behavioral health therapists on campus.

“We have the support, should there be any trauma,” she said. “Our school counselors are really, really good about talking stories with the students and being able to get to the bottom of problems.”

The end of the last school year was a “whirlwind,” Payne-Arakaki said.

With eruption activity happening during end-of-the-year assessments, academic coach Amber Makuakane said it was “kind of chaotic” trying to make sure students were in attendance and assessed.

She said it was a challenge to make “sure when they’re here, their needs are being met, too, knowing that they all have personal issues, which I can relate to because I’m going through the same thing. It was kind of crazy just making sure we were meeting the needs of our kids.”

Makuakane has worked at the school 12 years and was among the first who lost their homes to the Kilauea eruption. She and her two children, who also attend the school, evacuated May 3 from their Leilani Estates home. Just minutes after she got home from school, she received notice that the first fissure had opened and they would have to leave.

“It was a pretty chaotic and hectic hour or so,” Makuakane said. “There were helicopters flying all over; you could hear the popping of the fissure; you could hear the cars and trucks screeching down the highway trying to get to family and friends’ houses to try and get them to evacuate. My phone was ringing off the hook with text messages and phone calls of people trying to get a hold of me to see if I needed help.”

She said she hurried to gather important paperwork and tossed clothes for her and her two children, ages 4 and 7, into a trash bag, and “threw it all in the car, and then we left,” she said. “Of course, that was the last time I would ever see my home again.”

That night, fissure 2 opened across the street from her driveway.

“When I had left that Thursday night, I left knowing there was a possibility that that would be the last time I would see my home, and in that case, in order to be strong for my kids, I needed to be OK with that, and I needed to know that if this was going to be the next chapter in my life, then so be it,” Makuakane said.

After the evacuation, the next thing on her mind was finding a place for her and her children to stay because she was staying with a friend at the time.

“So, basically, I wasn’t able to return to work for at least two and a half weeks because that became my new full-time job,” Makuakane said.

Finding work and settling elsewhere wasn’t an option. Born and raised in Pahoa, Makuakane went to school in Pahoa, too.

“Being able to come back to the school that I graduated from is definitely an honor and privilege,” Makuakane said. “So when I think about the question of where do I work, this is where I want to work. This is where I belong, regardless of the situation and circumstances that surround us. We’re a very tight-knit community. We stick together through the thick and the thin. … It just makes me want to work even harder, especially knowing the things that our students are going through.”

Makuakane said kids are resilient and more adaptive to change than adults.

“I think that’s what we do as a school, as well,” Payne-Arakaki said. “You want everything to go back to normalcy as soon as possible because you don’t want to dwell on something because you want to be able to push forward. The students want to be here … I think just having their friends (and) being able to see the normal faces, even though they’re facing some sort of trauma within themselves.”

Better prepared

Payne-Arakaki said during the summer break, more systems were put in place to address student safety.

The school has a sulfur dioxide, or SO2, action plan, a school “particulate matter” action plan and even an ash action plan.

“Ash is not too much of a concern in our area, but it is a concern in the Ka‘u area,” Payne-Arakaki said. “But these action plans were all revised and developed with the (state Department of Education) and the Department of Health, so that way everybody’s on the same page, and I think that’s really good.”

According to Payne-Arakaki, the eruption has had little impact on overall enrollment thus far.

“I think when the volcano first started in May, we saw kind of like a mass exodus,” Payne-Arakaki said. “There were lots of parents disenrolling their children, moving back to the mainland, moving to the Kona side. … It was fear of the unknown, I think.”

But enrollment numbers this week weren’t far off projected counts, she said, with an estimated enrollment of 387 and an actual enrollment of 384 on Monday.

And with Hurricane Hector looming large in the Pacific, Makuakane likened it to the 2014 lava flow and Tropical Storm Iselle.

Payne-Arakaki said preparation comes back, again, to being informed.

“I think the learning we’ve done within the last couple of years through all of that, has really, really helped. So are we ready for a Hector?” Payne-Arakaki asked, before answering with a laugh. “Well, I think we can say we’re as ready as we’ll ever be. … With Mother Nature, you never know one way or another, but should something really bad happen, I know we, as a community, as a school, as a state, would be able to support each other and push through that, like we’ve done so far with the lava.”

Email Stephanie Salmons at ssalmons@hawaiitribune-herald.com.