Fraud and ineptitude are undermining COVID relief

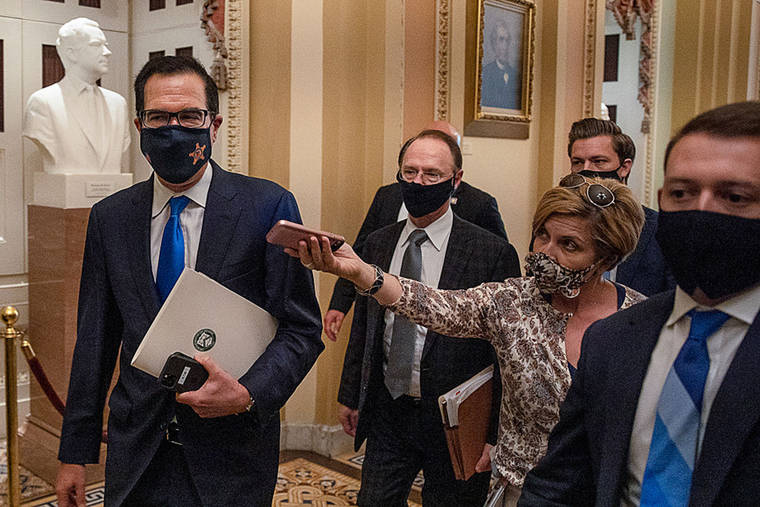

U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin departs from the office of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) at the U.S. Capitol on September 30, 2020 in Washington, DC. Mnuchin met with Democrats and Republicans about coronavirus relief legislation. (Photo by Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images/TNS)

How easy is it to steal federal funds meant for jobless Americans struggling to survive the COVID-19 economy? It’s this easy:

How easy is it to steal federal funds meant for jobless Americans struggling to survive the COVID-19 economy? It’s this easy:

“Using huge databases of stolen personal information, cybercriminals based everywhere from Nigeria to London have pocketed an estimated $8 billion meant for people forced out of work due to the coronavirus so far,” wrote Katy Murphy and Rebecca Rainey in Politico on Monday.

ADVERTISING

That’s probably just the tip of the iceberg. In an August report, the Labor Department’s inspector general said at least $26 billion of the $260 billion in extra federal support Congress steered toward unemployed workers since last spring will get scooped up by scammers.

A major reason worker aid is getting stolen, according to Murphy and Rainey’s reporting, is that state employment agencies charged with distributing the funds locally are running outdated systems that aren’t very good at vetting aid applications. Congress also permitted federal aid applicants to get funds without having to fully verify their identities. Fraudsters around the globe have found it easy to gin up names of phony employers, apply for funding and make off with their loot before anyone is the wiser. While state agencies have caught some of these criminals, the unprecedented volume of scams has allowed for lots of successful pickpocketing.

The Labor Department’s inspector general also pointed out another reason Congress is at fault: In its well-intentioned rush last spring to provide COVID-19 relief — the most massive federal rescue program of the post-World War II era — federal legislators failed to give states adequate guidance about how to anticipate and combat fraud.

As lawmakers and the White House still struggle to get their arms around the scope and scale of another round of much-needed federal relief for workers and their families, plugging holes in the system should be front of mind. A new agreement among Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell seems a long way off, but haphazard oversight of huge amounts of federal funding has scarred the effort ever since it was launched.

Remember all that Paycheck Protection Program funding that was meant to help small businesses but somehow found its way into the hands of publicly traded companies such as Shake Shack Inc., large operators such as McDonald’s franchisees, sports behemoths such as the Los Angeles Lakers and insiders in the federal government? How did that happen? Well, the federal apparatus Mnuchin runs and which doles out the funds hasn’t been minding the store. It’s not much more complicated than that.

According to a recent Washington Post analysis of $4 trillion of CARES Act funding — a sum that exceeds the cost of the 18-year-old war in Afghanistan — workers received only about $884 billion, or roughly one-fifth the total amount. Huge piles of money went to affluent Americans or companies that laid off the very workers the federal aid was meant to protect. A full accounting of how $670 billion in PPP funding was allocated hasn’t been completed, but as the Post noted, companies were not “compelled to use it to protect paychecks — and many didn’t.”

A Bloomberg News analysis in July noted that the applications for some 4.9 million PPP loans that were distributed at that point were riddled with perplexing, non-standardized responses that made it difficult to track how the money was allocated. Jobs numbers associated with at least 20% of the PPP loans were dubious.

It’s still not clear to me why the Treasury Department didn’t make direct PPP payments to workers rather than involve business owners, the SBA and banks as intermediaries. Every extra conduit in the process adds to its complexity and therefore to the possibility of errors or fraud.

For example, JP Morgan Chase & Co., one of the biggest banks involved in distributing PPP funds to qualified recipients, recently disclosed that it’s investigating whether some of its own employees might have illegally abetted schemes involving the misuse of the funds. In an internal memo, the bank said it has seen “instances of customers misusing Paycheck Protection Program loans, unemployment benefits and other government programs” and that some “employees have fallen short, too.”

Clearly, the process for distributing aid needs to be more transparent and have more sophisticated oversight than it’s had so far.

At the very least, states need technology upgrades and federal resources to combat fraud. In an August report, the Labor Department’s inspector general recommended that one of the agency’s divisions, the Employment and Training Administration, take four other steps: partner more closely with employers to monitor applicants’ qualifications, provide better oversight, get more accurate estimates of the scale of improper payments and require states to help detect fraud by providing access to unemployment claims data.

These common-sense recommendations will continue to be important if another big round of COVID-19 relief passes. States and the federal government have a responsibility to make sure that expensive COVID-relief programs — funded by taxpayers — are protected.

Timothy L. O’Brien is a senior columnist for Bloomberg Opinion.