Report: More than 25% of missing girls in state are Native Hawaiian

PAUOLE

KAPELA

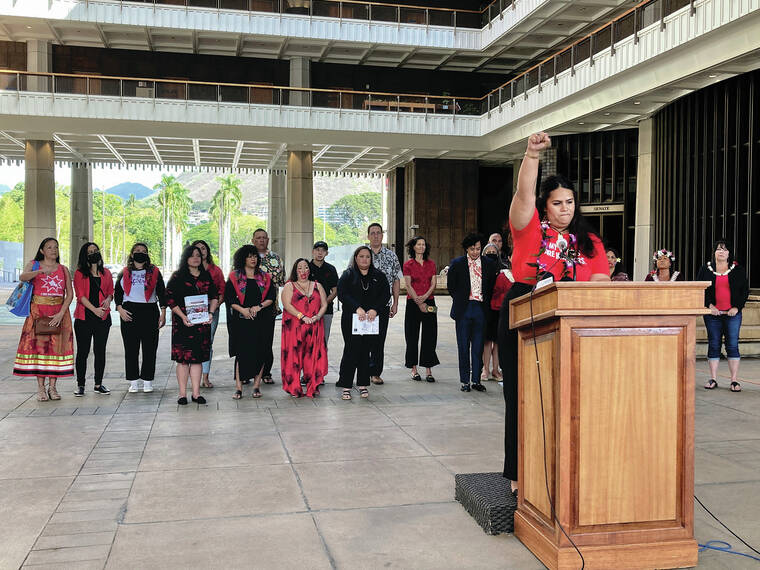

Makanalani Gomes, of AF3IRM, a feminist and decolonization organization, holds a fist in the air as she discusses a report on missing and murdered Native Hawaiian women, Wednesday, Dec. 14, 2022 in Honolulu. (AP Photo/Jennifer Sinco Kelleher)

A study released Wednesday found that Native Hawaiian women and girls “experience violence at rates disproportionate to their population size.”

A study released Wednesday found that Native Hawaiian women and girls “experience violence at rates disproportionate to their population size.”

The report, titled “Holoi a nalo Wahine ‘Oiwi: Missing and Murdered Native Hawaiian Women and Girls Task Force Report (Part 1),” was the first of a two-part report.

ADVERTISING

The task force, created by the state Legislature in 2021, is administered through the Hawaii State Commission on the Status of Women and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. It’s comprised of individuals representing over 22 governmental and nongovernmental organizations across Hawaii that provide services to those who are impacted by violence against Native Hawaiians.

According to the report, more than a quarter of the missing girls 17 and younger in Hawaii are Native Hawaiian, although Native Hawaiian females represent only 10.2% of the state’s population.

The report described the average profile of a missing child in Hawaii as a 15-year-old Native Hawaiian female missing from Oahu. It also finds 43% of sex trafficking cases are Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) girls trafficked in Waikiki, on Oahu.

“The fact that the Hawaiian population is disproportionately impacted by sexual violence is not an accident of history. On the contrary, it is a symptom of the colonial sickness that continues to infect Hawaii’s social system,” state Rep. Jeanne Kapela, a Big Island Democrat whose district stretches from Keaau to South Kona, said in a statement. “Just as our ‘aina is suppressed by the violence of militarization, so, too, are the islands’ native people subjected to the gender violence that stems from the imposition of Western patriarchy.”

On Hawaii Island, the report found that from 2018 to 2021, there were 182 cases of missing Native Hawaiian girls, more than from any other racial group. In addition, according to the report, Native Hawaiian children ages 15 to 17 reported missing in Hilo represent the highest number of missing children’s cases on the island, attributing the data to the Hawaii Police Department.

The report “broadly defined” the term “missing,” including Native Hawaiian girls younger than 18 “who are deemed as ‘runaways’ by law enforcement, meaning they may or may not return.”

Hawaii Police Department Lt. Robert Pauole of the Area I Juvenile Aid Section in Hilo said he believes the vast majority of cases cited are runaways, and police view their cases as different than those of missing persons.

“Currently, right now, we have only one missing child, and that’s Benny Rapoza,” Pauole said. “Anyone else is considered a runaway.”

Rapoza, a nonverbal autistic boy, was 6 when he disappeared from his Keaukaha home on Dec. 20, 2019.

The report’s definition of “missing” also includes “Native Hawaiian women and girls whose whereabouts are unknown, including women and girls who are missing as a result of being trafficked and/or trapped in the military-prostitution complex.”

The report highlights the case of Marlo Moku, a Native Hawaiian mother of three who disappeared at age 33 on Sept. 23, 2008.

Moku’s blue 1995 Chevrolet Corsica four-door sedan was found about three weeks later by fishermen at the bottom of a cliff near Hakalau Mill.

“Evidence suggests there did not appear to be a person inside the vehicle when it rolled off the cliff. Searches for Marlo Moku have been unsuccessful. Marlo Moku’s case remains open and unsolved,” the report states.

Also highlighted is the case of Lisa Au, a high-profile unsolved Oahu murder case from 1982.

Au’s case is classified by Honolulu police as a murder, but the study also used a definition of murder expanded “beyond governmental definitions … to center the experiences of survivors and move toward community healing in a way that is accurate and successful,” the report states. The expansion “includes Native Hawaiian women and girls who died under suspicious and/or complex circumstances such as drug overdose and suicide.”

According to the report, the expanded definitions “allow for the accuracy of exploring and naming the specific mechanisms of the MMNHWG crisis such as sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse, suicide, poverty and disenfranchisement from the land.”

The report concedes that “statistics on MMNHWG are highly limited,” and said that due to “a lack of accessible data and a systemic disregard for the safety and well-being of Native Hawaiian women and girls on the part of government entities” the report “must be interpreted with the understanding that the true scope of the problem of MMNHWG is much larger than the meager data available can demonstrate at this time.”

“The spirits of our stolen sisters are slipping through the pukas in our system. This report is a modest step in addressing violence against Kanaka Maoli women and girls,” said principal investigator Nikki Cristobal, co-founder and executive director of Kamawaelualani, a Kauai nonprofit corporation.

The group plans a second report “based on in-depth qualitative research in the community.”

Kapela said the report’s findings should “motivate us to demand stronger protections for survivors of sexual exploitation, institute proper training to empower more people to prevent violence before it happens, and champion visionary public policy that delivers compassion for Hawaii’s indigenous people and our land.”

Email John Burnett at jburnett@hawaiitribune-herald.com.