Sides square off on TMT: At stake is permit that will allow project to proceed

CHANG

Lincoln Ashida

Lanny Sinkin

Ross Shinyama

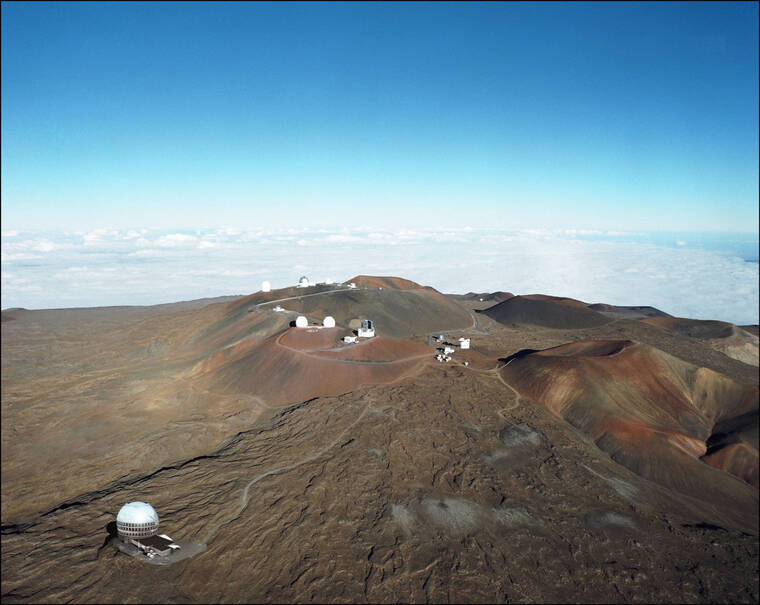

Photo courtesy TMT An artist's rendering shows the position of the Thirty Meter Telescope, seen on the bottom-left, in comparison to the other telescopes on Maunakea's summit.

Impassioned arguments were raised, but no conclusions were reached Tuesday during a hearing about whether the Thirty Meter Telescope has met minimum requirements to keep its land use permit for Maunakea.

Impassioned arguments were raised, but no conclusions were reached Tuesday during a hearing about whether the Thirty Meter Telescope has met minimum requirements to keep its land use permit for Maunakea.

The state Board of Land and Natural Resources heard oral arguments Tuesday from TMT attorneys and Native Hawaiian groups disputing whether construction on the controversial observatory has actually begun.

ADVERTISING

At the center of the debate was Condition No. 4, a requirement attached to a Conservation District Use Permit the BLNR granted to TMT in 2017 that allows the observatory to utilize land on the mountain’s summit.

The condition required that work begin on Maunakea within two years of the permit’s issuance — a deadline that was extended in 2019 when then-Department of Land and Natural Resources Chair Suzanne Case granted a two-year extension because of the Maunakea Access Road protests that were ongoing at the time.

But in 2021, when the deadline came up again, Case determined that minor site work done in 2019, including the removal of unpermitted ahu, site surveys and moving vehicles to the project location, was sufficient to satisfy Condition No. 4.

Several groups have challenged that determination, leading to a 2021 joint petition by several Hawaiian cultural practitioners and nonprofit group Kahea: The Hawaiian-Environmental Alliance, referred to collectively as the Mauna Kea Hui.

Both sides were able to present their arguments Tuesday.

Attorney Richard Wurdeman, representing the Mauna Kea Hui, said flatly TMT’s argument that work has begun relies on an “absurd” reading of DLNR rules that cannot be reasonably inferred to be intentional.

“Clearly, there has been no construction,” Wurdeman said. “Construction is, as we’ve stated in the dictionary definition, the building of something, typically a large structure. There’s been no grading up there, no pouring concrete. There’s not been any of that done here.”

Wurdeman went on to say Case acted “arbitrarily and capriciously” in her 2021 determination, noting the work she claimed satisfied Condition 4 predated the 2019 extension of the deadline.

“There’s been nothing new following the July 30, 2019, issuance,” Wurdeman said.

With Condition 4 seemingly unmet, Wurdeman concluded, TMT’s Conservation District Use Permit should be considered void.

Other Mauna Kea Hui petitioners made similar points. Attorney Lanny Sinkin pointed out that other TMT proponents — specifically a nonprofit of pro-TMT Native Hawaiian advocates called Perpetuating Unique Educational Opportunities Inc., whose arguments were included as joinders to TMT’s — argued the 2019 protests prevented TMT from initiating construction, which he said contradicts TMT’s claim that construction has begun.

Another petitioner, E. Kalani Flores, said TMT’s activities that supposedly satisfied Condition 4 — meetings, site surveys, vehicle inspections — would be considered “preconstruction activities” by anyone involved in the construction industry.

“These are not construction activities. It doesn’t matter if you have a construction contract,” Flores said. “Anybody involved in construction knows this.”

Flores added that a 2020 document by the U.S. Department of Health — when evaluating whether to grant TMT a pollutant discharge permit — determined there had been “no construction activity at the project site” since 2014.

“Whether it’s built or not built, you have to follow these conditions,” Flores said. “These are positions that the board approved. Whether it’s TMT or any other project are now given the ability to skirt around fulfilling certain project conditions, then where are we at? Where’s the trust in this agency?”

On the other side of the argument, attorney Ross Shinyama, representing TMT, said Condition 4’s exact language states “any work done or construction to be done on the land shall be initiated within two years” of the permit’s approval.

That fourth word, “or,” is key to interpreting the condition, Shinyama said, as it allows for “any work done” to be interpreted as distinct from “construction,” and so TMT’s work at the site satisfied Condition 4.

Lincoln Ashida, attorney for PUEO, agreed, adding that TMT obtaining permits from Hawaii County alone was “no easy feat.”

Ashida and Shinyama both raised an “unclean hands” argument — a legal doctrine wherein a party that might have acted improperly or in bad faith is not entitled to a legal remedy. In particular, they suggested the 2019 interference caused by the protests on Maunakea Access Road — which several Mauna Kea Hui members admitted to being involved in — constituted such impropriety.

Sinkin, countering that point, said TMT could not claim to be surprised by the 2019 protests, as it had conducted extensive risk assessments that identified the project as widely unpopular among Native Hawaiians and proceeded with clear knowledge of the potential for work interference that could prevent the fulfillment of Condition 4.

BLNR members questioned all parties who testified, but seemed to probe the TMT representatives more closely.

BLNR Chair Dawn Chang questioned whether the TMT project as it currently exists is still the same project the Conservation District Use Permit was awarded to in 2017.

“In light of (the National Science Foundation) maybe providing funds to the project … is the project that TMT is pursuing, is that the project that the land board approved?” Chang asked, to which Ashida responded in the affirmative.

Chang also noted that Condition 4 requires all work to be completed within 12 years of the issuance of the permit, which seems increasingly unlikely to happen, particularly now that the project must fulfill additional requirements for federal NSF funding.

Shinyama acknowledged this, and said TMT likely will be pursuing extensions to that 12-year deadline in the future.

In the end, the BLNR reached no verdict,because only oral arguments were heard Tuesday.

Chang said both parties have 40 days to submit proposed orders to the board, whereupon the BLNR will review the material and come to a decision at an undetermined date.

Email Michael Brestovansky at mbrestovansky@hawaiitribune-herald.com.