Trump declares US opioid emergency but pledges no new money

WASHINGTON — In ringing and personal terms, President Donald Trump on Thursday pledged that “we will overcome addiction in America,” declaring opioid abuse a national public health emergency and announcing new steps to combat what he described as the worst drug crisis in U.S. history.

ADVERTISING

Trump’s declaration, which will be effective for 90 days and can be renewed, will allow the government to redirect resources in various ways and to expand access to medical services in rural areas. But it won’t bring new dollars to fight a scourge that kills nearly 100 people a day.

“As Americans we cannot allow this to continue,” Trump said in a speech at the White House, where he bemoaned an epidemic he said had spared no segment of society, affecting rural areas and cities, rich and poor and both the elderly and newborns.

“It is time to liberate our communities from this scourge of drug addiction,” he said. “We can be the generation that ends the opioid epidemic.”

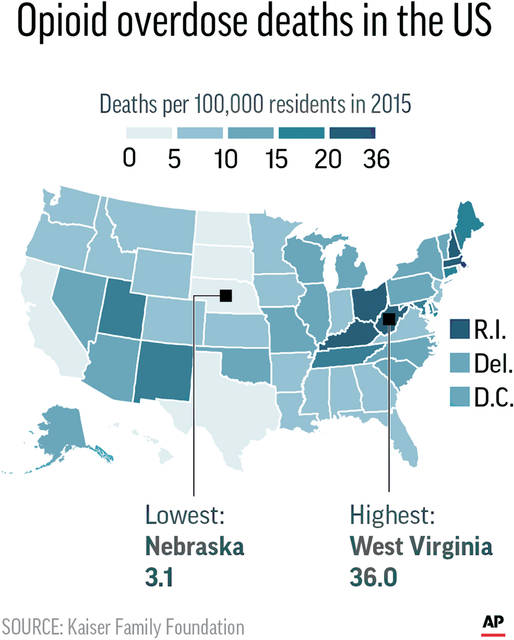

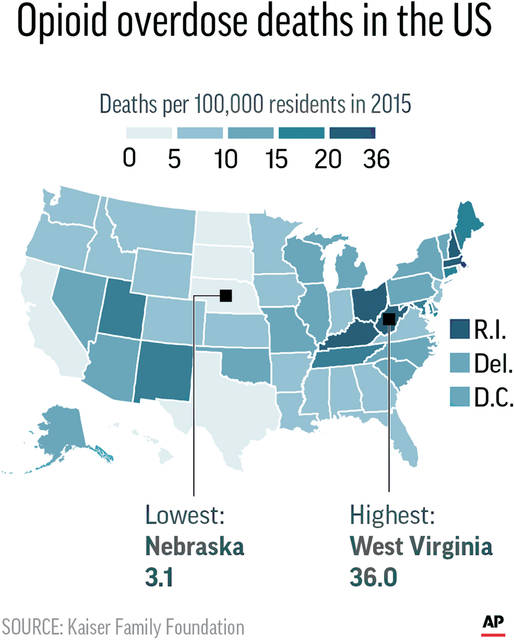

Deaths have surged from opioids, which include some prescribed painkillers, heroin and synthetic drugs such as fentanyl, often sold on the nation’s streets.

Administration officials said they also would urge Congress, during end-of-the year budget negotiations, to add new cash to a public health emergency fund that Congress hasn’t replenished for years and contains just $57,000.

But critics said Thursday’s words weren’t enough.

“How can you say it’s an emergency if we’re not going to put a new nickel in it?” said Dr. Joseph Parks, medical director of the nonprofit National Council for Behavioral Health, which advocates for addiction treatment providers. “As far as moving the money around,” he added, “that’s like robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

Democratic House leader Nancy Pelosi said, “Show me the money.”

Trump’s audience Thursday included parents who have lost children to drug overdoses, people who have struggled with addiction, first responders and lawmakers.

Trump also spoke personally about his own family’s experience with addiction: His older brother, Fred Jr., died after struggling with alcoholism. It’s the reason the president does not drink.

Trump described his brother as a “great guy, best looking guy,” with a personality “much better than mine.”

“But he had a problem, he had a problem with alcohol,” the president said. “I learned because of Fred.”

Trump said he hoped a massive advertising campaign, which sounded reminiscent of the 1980s “Just Say No” campaign, might have a similar impact.

“If we can teach young people, and people generally, not to start, it’s really, really easy not to take ‘em,” he said.

It’s a path taken by previous presidents, including Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, all of whom tried to rally the nation to confront drug abuse but fell short of solving the problem. Some people have become hooked on opioids after being prescribed prescription pain killers by doctors after injuries or surgery.

As a presidential candidate, Trump had pledged to make fighting addiction a priority. Once in office, Trump assembled a commission, led by Gov. Chris Christie of New Jersey, to study the problem. The commission’s interim report argued an emergency declaration would free additional money and resources, but some in Trump’s administration disagreed.

“What the president did today was historic and it is an extraordinary beginning set of steps to dealing with this problem,” Christie told reporters at the White House after the speech.

Some also faulted the White House for not issuing a wider emergency declaration to deal with the crisis.

Rob Brandt, an Ohio man who lost his 20-year-old son to a heroin overdose in 2011, called Trump’s public health emergency order a “good incremental step” but urged greater focus on prevention and long-term treatment.

“The federal government has lagged behind in truly decisive action,” said Brandt, who opened an opioid recovery center in Medina, Ohio this year, run on private donations and grants.

“We lost 64,000 Americans last year,” he said, “and if you look at, if we were to have a foreign country attack us and kill 60,000 Americans or a terrorist attack that killed 60,000 Americans, we would print money to combat that.”

As a result of Trump’s declaration, officials will be able to expand access to telemedicine services, including substance abuse treatment for people living in rural and remote areas. Officials will also be able to more easily deploy state and federal workers, secure Department of Labor grants for the unemployed, and shift funding for HIV and AIDs programs to provide more substance abuse treatment for people already eligible for those programs.

Trump said his administration would also be working to reduce regulatory barriers, such as one that bars Medicaid from paying for addiction treatment in residential rehab facilities larger than 16 beds. He spoke of ongoing efforts to require opioid prescribers to undergo special training, the Justice Department’s targeting of opioid dealers and efforts to develop a non-addictive painkiller.

Trump said one specific prescription opioid, which he described as “truly evil,” would be withdrawn immediately from the market. White House spokesman Hogan Gildey later said he was referring to the painkiller Opana ER. That drug was pulled from the market in July at the Food and Drug Administration’s request following a 2015 outbreak of HIV and hepatitis C in southern Indiana linked to sharing needles to inject the pills.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., said Trump’s effort falls far short of what is needed and will divert staff and resources from other vital public health initiatives.

“Families in Connecticut suffering from the opioid epidemic deserve better than half measures and empty rhetoric offered seemingly as an afterthought,” he said in a statement. He argued, “An emergency of this magnitude must be met with sustained, robust funding and comprehensive treatment programs.”

Democrats also criticized Trump’s efforts to repeal and replace the “Obamacare” health law. Its Medicaid expansion has been crucial in confronting the opioid epidemic.

Adopted by 31 states, the Medicaid expansion provides coverage to low-income adults previously not eligible. Many are in their 20s and 30s, a demographic hit hard by the epidemic. Medicaid pays for detox and long-term treatment.

Trump, meanwhile, tempered expectations even as he projected hope.

“Our current addiction crisis, and especially the epidemic of opioid deaths, will get worse before it gets better. But get better it will,” he said. “It will take many years and even decades to address this scourge in our society, but we must start in earnest now to combat national health emergency.

“Working together,” he said, “we will defeat this opioid epidemic. … We will free our nation from the terrible affliction of drug abuse. And, yes, we will overcome addiction in America.”

Featured Jobs

Featured JobsTrump declares US opioid emergency but pledges no new money

Associated Press

President Donald Trump shakes hands with New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie after signing a presidential memorandum Thursday in the East Room of the White House declaring the opioid crisis a national public health emergency.

WASHINGTON — In ringing and personal terms, President Donald Trump on Thursday pledged that “we will overcome addiction in America,” declaring opioid abuse a national public health emergency and announcing new steps to combat what he described as the worst drug crisis in U.S. history.

WASHINGTON — In ringing and personal terms, President Donald Trump on Thursday pledged that “we will overcome addiction in America,” declaring opioid abuse a national public health emergency and announcing new steps to combat what he described as the worst drug crisis in U.S. history.

Trump’s declaration, which will be effective for 90 days and can be renewed, will allow the government to redirect resources in various ways and to expand access to medical services in rural areas. But it won’t bring new dollars to fight a scourge that kills nearly 100 people a day.

ADVERTISING

“As Americans we cannot allow this to continue,” Trump said in a speech at the White House, where he bemoaned an epidemic he said had spared no segment of society, affecting rural areas and cities, rich and poor and both the elderly and newborns.

“It is time to liberate our communities from this scourge of drug addiction,” he said. “We can be the generation that ends the opioid epidemic.”

Deaths have surged from opioids, which include some prescribed painkillers, heroin and synthetic drugs such as fentanyl, often sold on the nation’s streets.

Administration officials said they also would urge Congress, during end-of-the year budget negotiations, to add new cash to a public health emergency fund that Congress hasn’t replenished for years and contains just $57,000.

But critics said Thursday’s words weren’t enough.

“How can you say it’s an emergency if we’re not going to put a new nickel in it?” said Dr. Joseph Parks, medical director of the nonprofit National Council for Behavioral Health, which advocates for addiction treatment providers. “As far as moving the money around,” he added, “that’s like robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

Democratic House leader Nancy Pelosi said, “Show me the money.”

Trump’s audience Thursday included parents who have lost children to drug overdoses, people who have struggled with addiction, first responders and lawmakers.

Trump also spoke personally about his own family’s experience with addiction: His older brother, Fred Jr., died after struggling with alcoholism. It’s the reason the president does not drink.

Trump described his brother as a “great guy, best looking guy,” with a personality “much better than mine.”

“But he had a problem, he had a problem with alcohol,” the president said. “I learned because of Fred.”

Trump said he hoped a massive advertising campaign, which sounded reminiscent of the 1980s “Just Say No” campaign, might have a similar impact.

“If we can teach young people, and people generally, not to start, it’s really, really easy not to take ‘em,” he said.

It’s a path taken by previous presidents, including Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, all of whom tried to rally the nation to confront drug abuse but fell short of solving the problem. Some people have become hooked on opioids after being prescribed prescription pain killers by doctors after injuries or surgery.

As a presidential candidate, Trump had pledged to make fighting addiction a priority. Once in office, Trump assembled a commission, led by Gov. Chris Christie of New Jersey, to study the problem. The commission’s interim report argued an emergency declaration would free additional money and resources, but some in Trump’s administration disagreed.

“What the president did today was historic and it is an extraordinary beginning set of steps to dealing with this problem,” Christie told reporters at the White House after the speech.

Some also faulted the White House for not issuing a wider emergency declaration to deal with the crisis.

Rob Brandt, an Ohio man who lost his 20-year-old son to a heroin overdose in 2011, called Trump’s public health emergency order a “good incremental step” but urged greater focus on prevention and long-term treatment.

“The federal government has lagged behind in truly decisive action,” said Brandt, who opened an opioid recovery center in Medina, Ohio this year, run on private donations and grants.

“We lost 64,000 Americans last year,” he said, “and if you look at, if we were to have a foreign country attack us and kill 60,000 Americans or a terrorist attack that killed 60,000 Americans, we would print money to combat that.”

As a result of Trump’s declaration, officials will be able to expand access to telemedicine services, including substance abuse treatment for people living in rural and remote areas. Officials will also be able to more easily deploy state and federal workers, secure Department of Labor grants for the unemployed, and shift funding for HIV and AIDs programs to provide more substance abuse treatment for people already eligible for those programs.

Trump said his administration would also be working to reduce regulatory barriers, such as one that bars Medicaid from paying for addiction treatment in residential rehab facilities larger than 16 beds. He spoke of ongoing efforts to require opioid prescribers to undergo special training, the Justice Department’s targeting of opioid dealers and efforts to develop a non-addictive painkiller.

Trump said one specific prescription opioid, which he described as “truly evil,” would be withdrawn immediately from the market. White House spokesman Hogan Gildey later said he was referring to the painkiller Opana ER. That drug was pulled from the market in July at the Food and Drug Administration’s request following a 2015 outbreak of HIV and hepatitis C in southern Indiana linked to sharing needles to inject the pills.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., said Trump’s effort falls far short of what is needed and will divert staff and resources from other vital public health initiatives.

“Families in Connecticut suffering from the opioid epidemic deserve better than half measures and empty rhetoric offered seemingly as an afterthought,” he said in a statement. He argued, “An emergency of this magnitude must be met with sustained, robust funding and comprehensive treatment programs.”

Democrats also criticized Trump’s efforts to repeal and replace the “Obamacare” health law. Its Medicaid expansion has been crucial in confronting the opioid epidemic.

Adopted by 31 states, the Medicaid expansion provides coverage to low-income adults previously not eligible. Many are in their 20s and 30s, a demographic hit hard by the epidemic. Medicaid pays for detox and long-term treatment.

Trump, meanwhile, tempered expectations even as he projected hope.

“Our current addiction crisis, and especially the epidemic of opioid deaths, will get worse before it gets better. But get better it will,” he said. “It will take many years and even decades to address this scourge in our society, but we must start in earnest now to combat national health emergency.

“Working together,” he said, “we will defeat this opioid epidemic. … We will free our nation from the terrible affliction of drug abuse. And, yes, we will overcome addiction in America.”